Philippians

In Philippians 2:1–13, Paul exhorts the Christians of Philippi to be of one mind and one love. The language of uniformity would appeal to Christians in this place because many of them were either veterans themselves or the descendants of Roman soldiers.

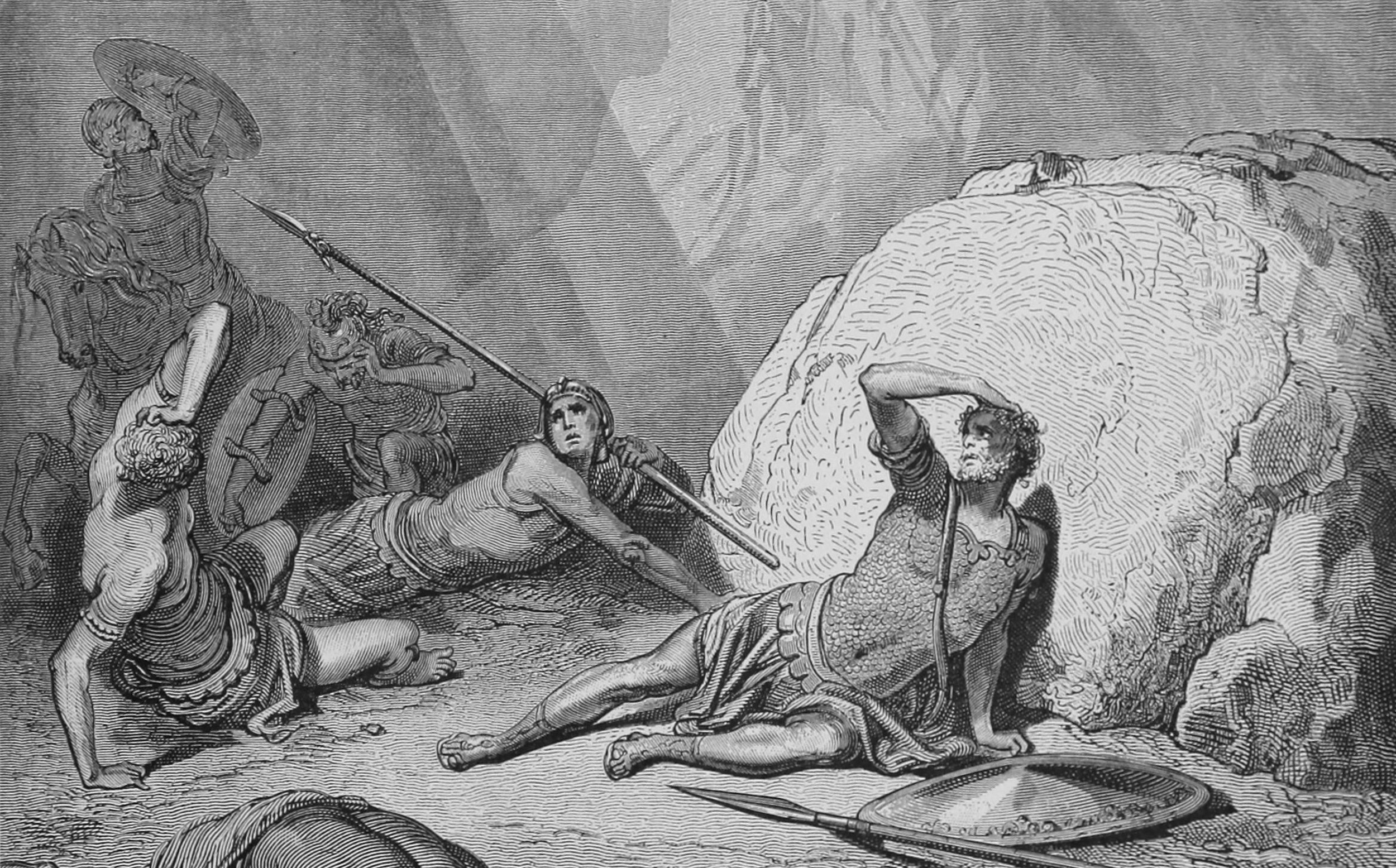

The town of Philippi is where Julius Caesar’s assassins, Marcus Junius (“you too?”) Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus fled before being caught by Caesar’s avengers, Mark Antony and Octavian. In 42 BC, the Battle of Philippi raged between a number of Roman legions loyal to either to Octavian or to Brutus. The victory went to Octavian, and the Republican assassins and their troops were annihilated. Rome had officially become an Empire…

It was customary at the time for entire legions to be raised and retired together. If their service was honorable, they were given plots of land and some money, the equivalent of modern veterans’ benefits. Octavian became emperor and retired most of his 28th Legion there in Philippi not long after the battle. In honor of their retirement, the city was renamed Colonia Victrix Philippensium, or “Victory Colony, Philippi.” Twelve years later, in 30 BCE, Octavian retired more veterans, this time from his secret service unit, the Praetorian Guard.

Ancient Philippi, of the Roman province of Macedonia

Paul references the Emperor’s elite guard in verses 1:12–13 “I want you to know, beloved, that what has happened to me has actually helped to spread the gospel so that it has become known throughout the whole imperial guard and to everyone else that my imprisonment is for Christ.” This verse is the only place in which this reference to the security force occurs in the New Testament. It’s noteworthy that Paul doesn’t reference it disapprovingly, either, because Paul knew his audience would see the protection of Caesar’s life as a good thing. In fact, many of them would have had fathers or grandfathers who served in that very unit.

Paul’s letter to the church in Philippi is usually dated in the late 50s AD, just 80 years after Octavian’s personal security detachment was retired there. Roman citizens were at the top of the social hierarchy in the provinces, so it is safe to assume the land stayed in their family and may have even been inhabited by the very next generation of those who had known the Roman military establishment so well. In fact, the town was ruled by two military commanders called duumviri appointed by those in the imperial capital, and was known informally as a “miniature Rome.” Any church born in Philippi would have identified very strongly with the military culture and customs of the time.

PAUL IS WRITING TO A MILITARY TOWN, AND HE KNOWS IT.

We shouldn’t read Paul’s address as just another letter to a house church on the outskirts of the empire. Paul is not writing to some relatively homogenous group that happens to be a bit more northern than the rest. Luke refers to Philippi specifically as a “Roman colony” in Acts 16:12 and it is where Paul and Silas are imprisoned. When the earthquake frees them, the Roman soldier guarding them tries to kill himself for failing at his job but Paul prevents the suicide.

In writing to Philippi, Paul is writing to a military town, and he knows it. He uses language with which soldiers are intimately familiar. Paul knows that soldiers count it a “privilege” to “[suffer] for” others (1:29), and refers to Epaphroditus as a “fellow soldier” (2:25) who Paul compliments by saying “he came close to death for the work of Christ, risking his life.” (2:30) Soldiers who are trained in the value of obedience would be encouraged by Paul’s reminder “just as you have always obeyed me…work out your own salvation with fear and trembling.” (2:12)

Social hierarchy and rank play an important role in his letter to them, reminding officers and enlisted alike that “If anyone else has reason to be confident in the flesh, [Paul has] more: circumcised on the eighth day, a member of the people of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew born of Hebrews; as to the law, a Pharisee.” (3:4b-5) What is unique here is that Paul flips martial meritocracy, insisting to the rigidly hierarchical veteran community that “whatever gains [Paul] had, these [he has] come to regard as loss because of Christ” (3:7) — it is no longer about acquisition and prestige in the empire of God, it is about forfeiture and humility.

Thanks to Roman roads across the empire, the Roman military was very mobile. Soldiers in most any unit would have been familiar with harsher tactics used in provinces known to be hostile, like Judea, where it was standard operating procedure to be dominating and in charge. When Paul admonished the descendants of this community to consider not being the top dogs, but to rather “consider others better than yourselves,” it might not have been the easiest pill to swallow. To a community accustomed to godlike status, to forcibly bending the insubordinate (indigenous) knee, Paul’s letter insisting that “every knee should bend” (2:10)… and “every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord” (2:11) probably carried a little sting for former soldiers who had confessed Octavian as lord.

As to the enemy that soldiers were so accustomed to engaging, “their glory is in their shame; their minds are set on earthly things.” (3:19) As for the veterans and their descendants in Philippi, they knew what it was to stand “firm in one spirit, striving side by side with one mind” (1:27) because they first learned how in their military training. But the letter to the veteran colony at Philippi is not the only place that soldiers have a part in the story of our faith, and it will not be the last.