Luke 3

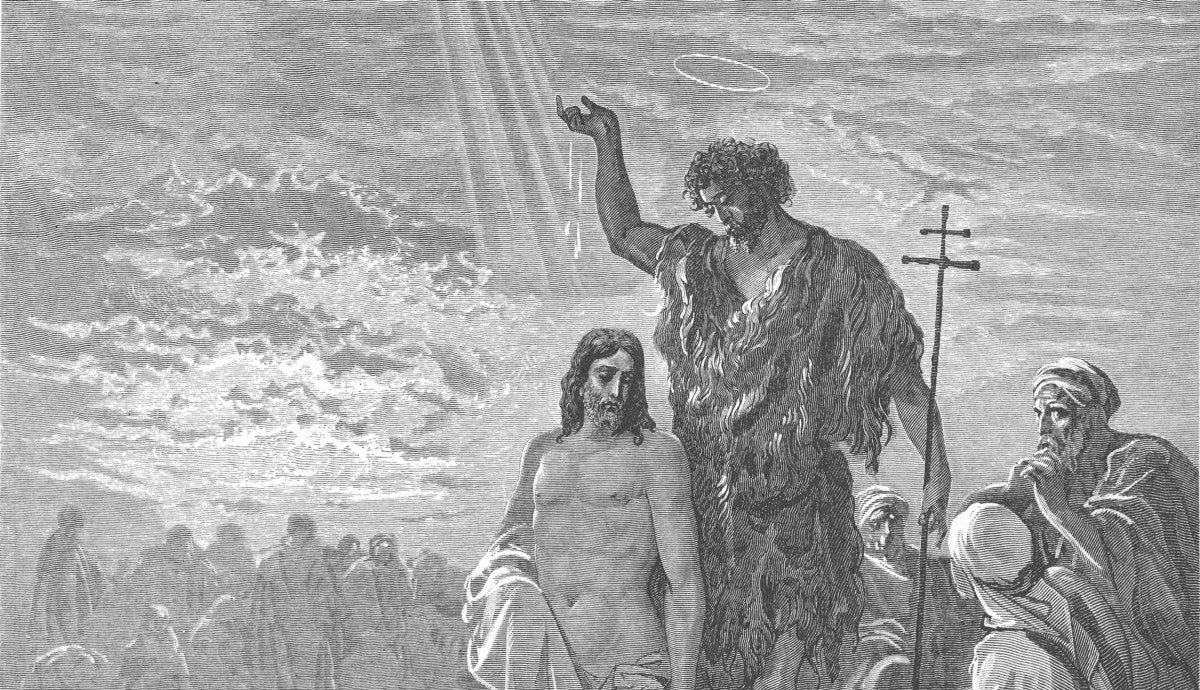

When Christians talk about soldiering, one passage that comes up often is from Luke’s gospel where John is preparing to baptize his cousin Jesus at the River Jordan (Luke 3:1–20). The thought process goes something like; “Jesus didn’t condemn these specific soldiers, so therefore he doesn’t condemn soldiering in general.” What more can this tale of the unnamed soldiers tell us about what is really going on?

The “few” soldiers are likely part of a small guard detail accompanying the tax collector mentioned in verse 12. This was common, even Herod Antipas had Roman soldiers assigned to protect him. The chief priests that plotted against Jesus had a Temple Guard that answered (more or less) to the religious establishment in Jerusalem — this is why soldiers accompany them to Gethsemane when it comes time to arrest Jesus. By no means are they conducting their otherwise more violent expression of statecraft we call “war.” This is not a passage about war and battle, but diplomacy and economics. They likely protected the tax collector from zealots, or enforced Rome’s claim to taxation (which Jesus does not challenge). The soldiers here are acting in something much more akin to a police role.

Also noteworthy is the word “soldiers” (strateuomenoi), rather than “centurion” (hekatontarchou). Centurions were commanders of 100 soldiers, and the socio-economic power dynamics should not be overlooked. Until the Marian reforms, which lasted as late as 27 CE, military service was compulsory meaning that soldiers were drafted involuntarily to fight or be assigned far away from their homes. Commanders and other mid-level professionals were typically wealthy or on their way to being wealthy. The strateuomenoi, therefore, were probably assigned to protect the tax collector without necessarily being supportive of ‘the system’ or of having a whole lot of power over it in the first place.

Mary & Joseph at the census, with tax collector and armed guards.

It should not surprise us, anyway, that God does not “bless the troops.” In fact, Jesus doesn’t say much of anything. It is John who speaks. When he does, he tells them to not falsely accuse people or to assist the tax collector in extorting money (which tax collectors were known for). After all, as representatives of Rome, they held all the cards, they could get away with murder. Soldiers often did just that. The very fact that the soldiers asked John what they should do suggests two possibilities:

They were taunting John, and his answer betrays their mockery with plain honesty (which makes them look like jerks, and this story warns us against being like them)

They saw this indigenous, camel-skin-suited fool as a legitimate authority and dispenser of wisdom (which doesn’t speak too highly of their armor-clad commander in chief…)

Finally, if you read the Gospels canonically, the answer from John the Baptizer might evoke particular stories from other Gospels, like the ending of the book of Matthew, namely chapter 28, vv.1–15. After Jesus is killed, the chief priests temporarily assign their Temple Guard to mortuary affairs to make sure that Jesus stays dead. When he doesn’t, the Tomb Guards report the resurrection to the chief priests (v.11), who bribe the soldiers into falsifying their report to Pilate (v.12) and thereby save their skins for apparently sleeping on the job. The soldiers “took the money and did as they were” told. (v.15)

If the soldiers had been “content with [their] pay,” as John instructs them, would they have taken the priests’ money to cover up their dereliction? Even if the events were not related, the formation of the canon does seem to imply the intent of the early church, and the connection between payments and the duties of soldiering is hard to miss. Additionally, Torah’s warning against bearing false witness should inform our assessment of the soldiers who lied to Pilate about disciples stealing Jesus’ body (but their social location should as well).

Soldiers, it seems, would have every bit as much of a reason to accompany the tax collector to the waters of baptism, for it is at the baptismal waters that one repents and turns away from their former lives. This may be the most honest interpretation since verses 7 and 10 have John addressing “the crowds” (including tax collectors and soldiers) as “you brood of vipers!” The Baptizer has no reason to think that the soldiers are there for anything less than baptism; the time has come for metanoia, for a change of command in their hearts.

Reading the story honestly requires that we approach it with an appreciation for John’s motives. Seeing tax collectors and soldiers approach the baptismal waters, already having uttered his typical upbraiding, why would he not assume the soldiers seek what he was there to offer, which was a baptism for the forgiveness of sins…?