What was Jesus’ real name?

If you've encountered my writing, you've probably noticed I use "Jesus" in scare quotes or write Joshua+ when referring to Mary's son, the messiah of Israel. This isn't pedantry—it's a theological and political choice about whose naming practices get to define the Son of God.

English speakers didn't get the name "Jesus" from Hebrew or Greek. We got it through a 4th-century Latin translation that the western Church, based in Rome, privileged throughout the middle ages. Saint Jerome transliterated the Greek Ἰησοῦς into Iesus, and then the I eventually became J. But Ἰησοῦς already had a Latin form: Iosue—Joshua. The formal Hebraic name Mary was instructed to give her baby was Yᵊhôšûaʿ. When you say "Jesus," you're using Rome's name for a Jewish messiah. When I write Joshua+, I'm refusing to let imperial translation override the compositional intent of a colonized people's text.

It's Joshua—And That Matters

The angel told Mary to name her son Yeshua (the shortened form of Yehoshua) "because he will save his people from their sins" (Matthew 1:21). The name isn't arbitrary—it describes what he came to do by connecting him to who in Israel's history already did it.

Yehoshua means "YHWH is salvation." It's also the passive participle of the Hebrew root verb yasa, "to save." The name itself literally means Salvation. And there are three Joshuas in Israel's scriptures whose roles combine to explain who Mary's son is and what he does;

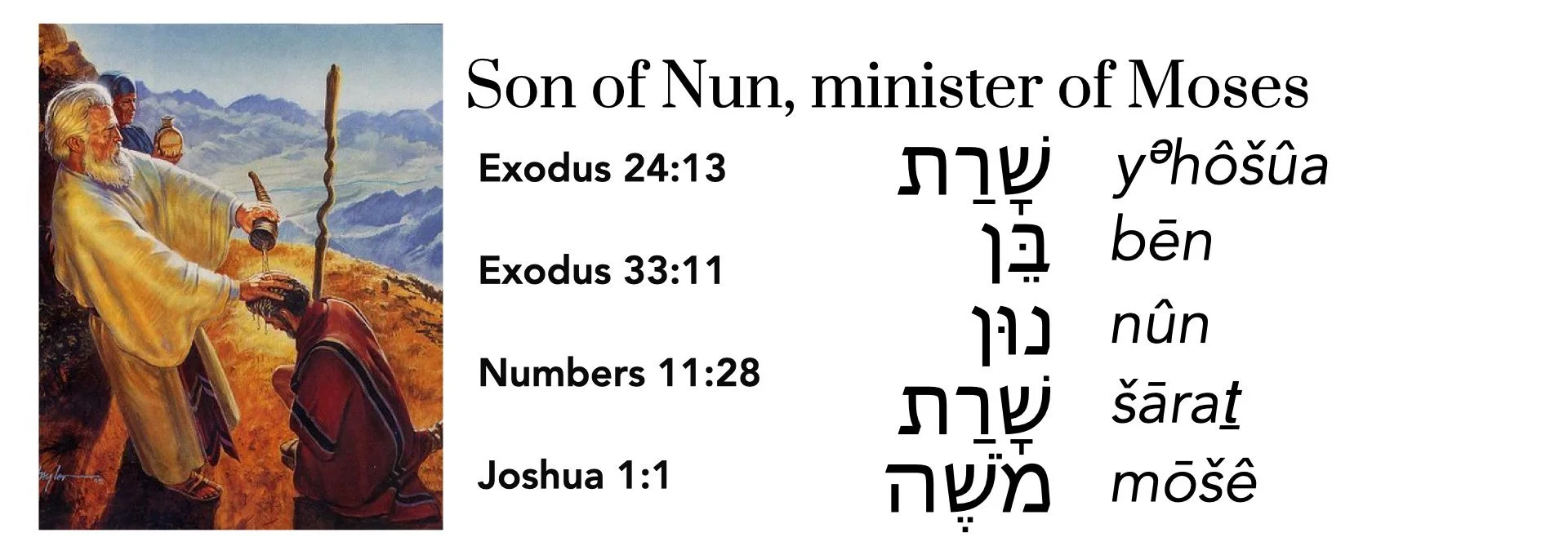

The Military Joshua (Yehoshua ben Nun) was Moses's minister who led Israel's army to conquer and distribute the Promised Land. Moses himself renamed this commander from Hoshea to Yehoshua in Numbers 13:16, adding the divine name Yah to "salvation." The book bearing his name records seven chapters of military campaigns.

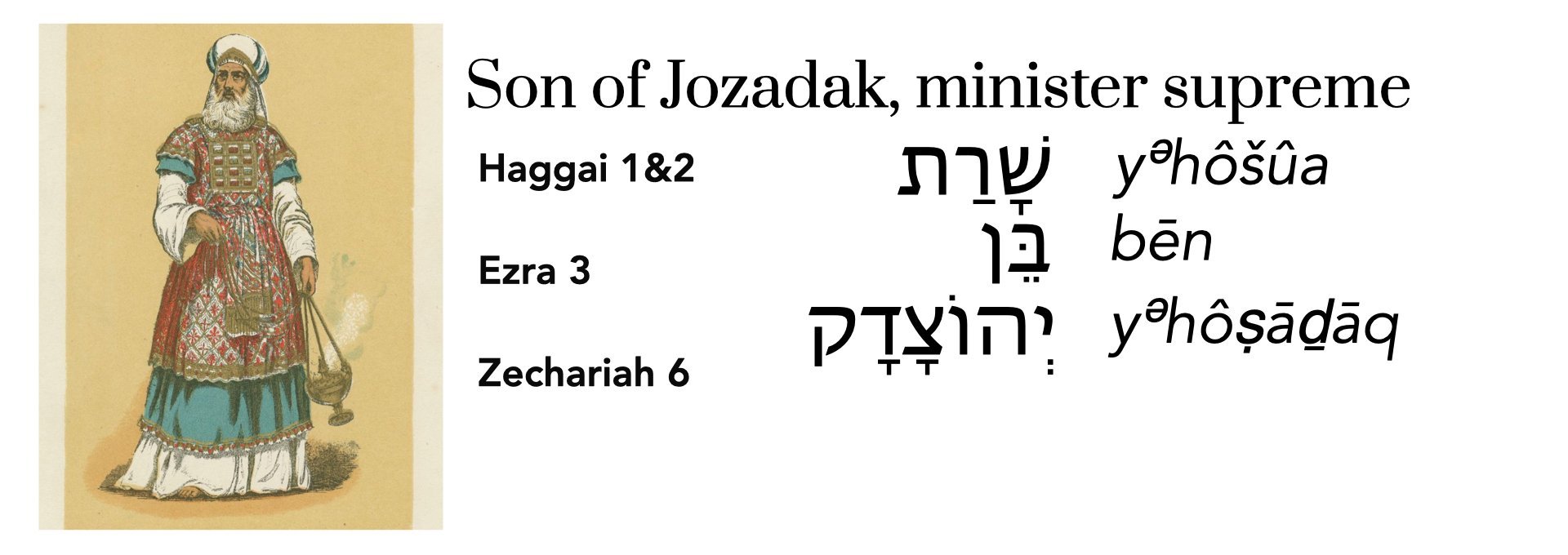

The Ministry Joshua (Yehoshua ben Jehozadak, shortened to Yeshua ben Yozadak) was the first High Priest after Babylonian exile. He oversaw building the Second Temple. In Zechariah 6:11, the prophet crowns him, making him the only ruler-priest in the Hebrew Bible—both military commander and religious minister.

The Messiah Joshua combined both roles. He's never clearly called ben Yosef (son of Joseph)—Luke 3:23 says "being the son (as was supposed) of Joseph," and Mark 6:3 has his hometown calling him "son of Mary" because that's all they knew for certain. But the name identifies his function perfectly.

The Nazar-ish Judge-Temple

After Joshua ben Nun distributed the Promised Land, Israel operated without kings. Instead, "the LORD raised up judges, who saved them out of the hand of those who plundered them" (Judges 2:16). The Judge served as military commander-in-chief of the saba Yehovah (army of God) when needed, but held no permanent political office—an ad-hoc system that prevented militarism by not maintaining a standing army.

Joshua ben Yehozadak's Temple stood in Jerusalem for hundreds of years until Herod "took away the old foundations" shortly before Mary's son was born (Josephus, Antiquities XV, 11.3). Perfect timing—a new Joshua was coming to wage spiritual warfare by building an everlasting Temple in and of his own person.

But Mark, the earliest Gospel, doesn't connect Joshua+ to the corrupted priesthood controlling Herod's Temple. Instead, Mark draws on Numbers 6—the Nazirite vow that allowed any Israelite to consecrate themselves directly to YHWH without Levitical mediation. This was hyper-priesthood of popular piety, circumventing the entire Temple economy the Sadducees had monopolized. Joshua+ doesn't restore their stranglehold on sacrifice and access to God. He embodies a more ancient, democratic holiness that bypasses their corruption entirely while simultaneously fulfilling the priestly role they'd perverted.

Joshua+ is Judge-commander of God's army and this Nazirite-type priest who makes the Temple establishment obsolete. He doesn't just lead military campaigns against Rome—he fights the cosmic battle against sin itself. He's not just the priestly minister—he's simultaneously the sacrificer and the slaughtered goat, rendering institutional control over atonement mechanisms irrelevant.

Why This Practice Matters

Calling the Christ "Jesus" obscures these connections. It treats the Gospels as if they began in Latin rather than emerged from Second Temple Jewish contexts. It centers Roman reception over Jewish composition, attributing the empire's theological framework to a colonized people's messianic literature.

When I write Joshua+ or "Jesus" in scare quotes, I'm insisting on reading these texts the way their authors composed them—as Jewish documents about Jewish hopes for salvation through a Jewish messiah whose very name connected him to Israel's judges and popular piety. The + indicates he's the fulfillment of all three Joshuas: military deliverer, priestly minister, embodied Temple.

If his name describes what he came to do, then using Rome's version instead of Israel's tells you who gets to define salvation. I choose the name his mother was told to give him, the name that made first-century Jews immediately think of liberation, priesthood, and the restoration of Israel's anti-imperial political imagination.

That's why I write it this way. Not because "Jesus" is wrong, exactly—but because it's Rome's choice, not Mary's.