From Anointment to Appointment

One of the things I’ve been exploring as I continue to think about the military in scripture is where they fit within the political entity that Israel represents. We sometimes think that Christ or Messiah is essentially a regnal title, like King, but that is not exactly how the story of the Bible depicts anointing.

King?

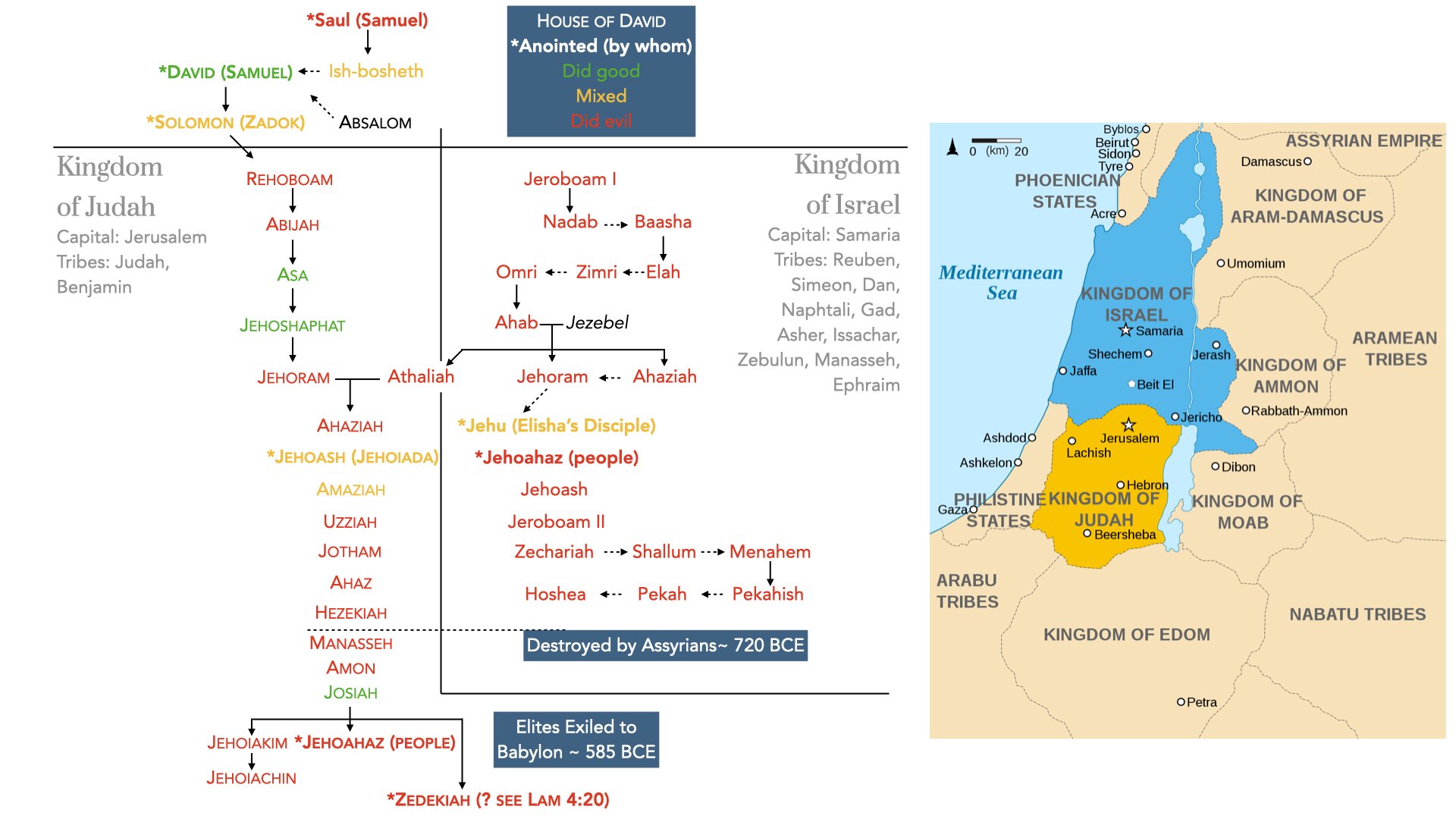

Sure kings were anointed, but not all of them, and not even most of them. Here’s a graphic I’m developing that shows all the kings of Israel and Judah;

I know it’s busy, but it’s still just a draft. In it, you can see that, even in the comparatively virtuous House of David and the southern Kingdom of Judah, only about a quarter of kings (6 out of 23) were anointed. In the northern Kingdom of Israel, that number falls to less than a tenth (2 out of 19).

This may be because kings were, within the Biblical narrative at least, a foreign concept to Israel. The time of the tribal confederation concludes with Samuel reluctantly anointing Saul after the people demanded a king “like all the nations.” (1 Sam 8:5) If Jesus is God’s Anointed, the Christ/Messiah, that office has only a very limited relationship with kingship. We see this in the Holy Family, in which the royal line of Judah, through Joseph, is in name only; David’s genes do not course through Jesus’ veins because Joseph is not Christ’s biological father.

Priest!

According to Luke, Jesus’ only biological affiliation is with the priestly, landless tribe of Levi. Mary and her blood relative (syngenēs, v.36) Elizabeth are both “from the daughters of Aaron” (v.5). That makes sense since anointing was a requirement of all priests, not least of which being the Aaronic High Priests. In contrast to the kings, the Bible depicts the High Priestly office as an unbroken hereditary line from Aaron, through Zadok (who anointed David), to “Jason” in 175 BCE.

The final Zadokite high priest was unpopular amongst devout Jews committed to ancient Israelite traditions. According to Josephus, “Jason” was the Hellenized name he took to appeal to Greek culture. Before the change, he was called יֵשׁוּעַ (Yēšūaʿ, anglicized to “Jesus”). He was deposed by the power-hungry Bejamite Menelaus and the Aaronic High Priesthood was brought to an end. Although it saw a resurgence under the Hasmonean dynasty, under Herod it became a political appointment rather hereditary.

When Jesus has his priestly showdown with Caiaphas, every Biblically literate Jew would have known Caiaphas was a Herodian puppet. It would have been to Caiaphas’ own embarrassment to suggest he was a legitimate heir to the High Priesthood. The other option, of a bastard child of an Aaronic harlot, was not satisfying either, but better a man of the people than an entitled little shit.

However corrupt the priesthood was or became, priests were all required to be anointed as part of their initiation. (see Exodus 40:12-15) That means we should think of Messiah more in priestly terms than royal ones. This is reinforced by Jesus’ genealogy, above. But priests and kings were not the only things anointed in Israelite or other ancient cultures.

Before Priests and Kings

The verb from which we get Messiah is māšaḥ, which in its oldest sense meant to paint or smear. The holy oil was smeared on the forehead of the messiah, whether priest or king. This was the same ritual that soldiers performed on defensive equipment to keep it from becoming brittle and weak. It is this sense in which māšaḥ is used in Isaiah 21:5; “Arise, O princes; oil the shield!” Long before Aaron or Saul, soldiers would anoint their shields as a kind of Preventive Maintenance Checks and Service (PMCS).

That makes the Holy Garments of the High Priest as the Armor of God all the more interesting. But if there is one takeaway from all this, it’s that Jesus is supposed to be the fulfillment of liturgical expectations rather than political ones. It also suggests that the political constitution of Israel is such that service, and soldiers, answer to God through the priests rather than the rulers. All this further solidifies in my mind that Biblical soldiering is far more liturgical than political. But anyway, that’s what’s been occupying my mind as I continue to think about God’s plan for the military and what it means to be a Christian soldier within its intended purpose and function. Thoughts?