Lydia the Purple Seller

Lydia the porphyropōlis, or purple-seller, features prominently in Acts 16 when Psaul is in Philippi during his 2nd missionary journey. Luke calls the city “a Roman colony” (v.12), which the Latin-speaking colonizers called Colonia Victrix, Victory Colony, because it was the birthplace of the Roman Empire. In 43 BCE, the plains surrounding Philippi served as the battlefield where Julius Caesar’s assassins were defeated by future emperors Octavian and Marc Antony. Philippi was to Romans what Appomattox is to Americans.

After their 20 years of service, legionaries would be allowed to marry and receive a plot of land in a colony where they were expected to help recruit and train the next military generation. Philippi’s special place in the imperial imagination meant only the most Roman of Romans could hope to raise a family and live out their days there. If Lydia owned property in the Victory Colony, it probably came to her through a light-skinned Italian veteran, the same through whom she would have received the only legal status women were afforded, as either a daughter or wife. In modern parlance, she was a military dependent.

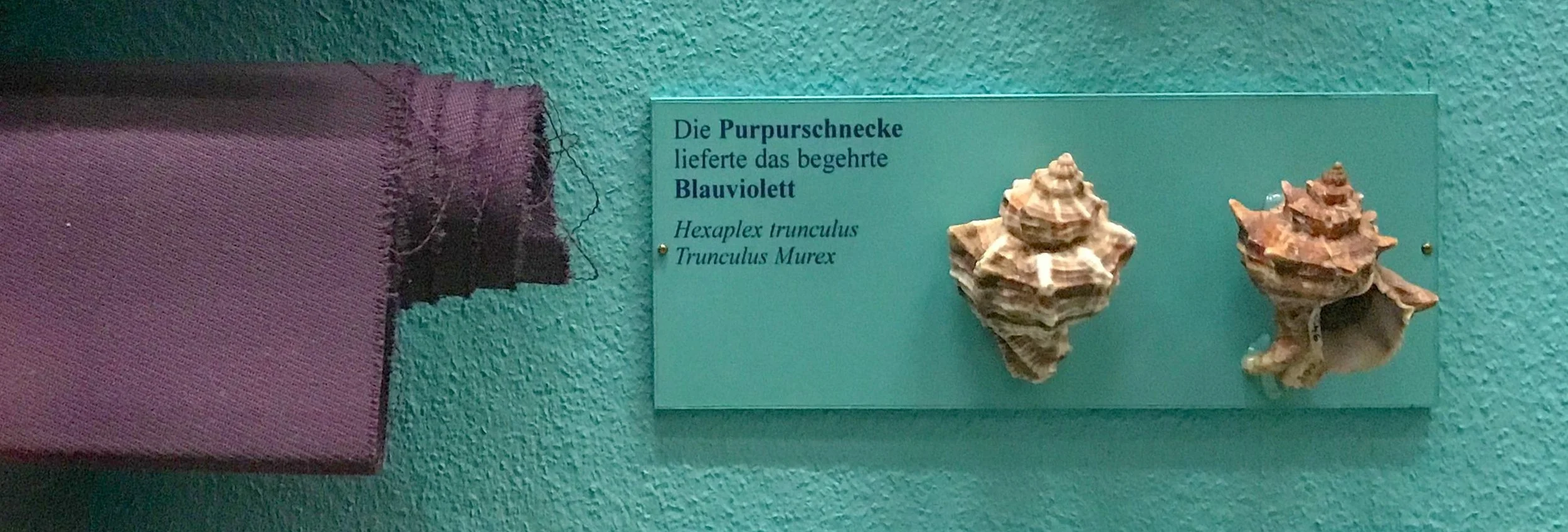

Like most military families, Lydia is familiar with displacement. She is from Thyatira, a city known as a hub of the Tyrian Dye trade. Its purple hue came from the mucus of sea snails, and its manufacture was labor intensive. “Royal Purple” was so valuable that it was reserved for wear by the imperial court. The only exception to this rule was Roman generals performing a ritual triumph after returning victorious from war. The exceedingly small but powerful market for the dye made porphyropōlia few and far between.

But an unattached female in the high-status world of imperial textiles? That only heightens the likelihood that Lydia built her wealth as part of a tight-knit family. The only lingering question, then, is what kind of dependent was she; a “brat” or a spouse? It was far more common for a man’s widow to maintain a business (and its attendant influence) than for his daughter, and the scholarly consensus is that she’s the former.

Lydia’s no Gold Star Wife, though; her guy wouldn’t have received the land until after an honorable discharge. That means they had a life together before he died, one they built using his connections to the imperial court and high-ranking military officers, as well as her knowledge of the posh textile economy of her hometown. What she offers to Psaul and his companions came to her, and by extension to him, through a particularly military economy.

We shouldn’t downplay or ignore the martial connotations of Lydia’s story and the significance of military families in the New Testament. Most Christians know Acts 10 features Cornelius, the centurion of Caesarea, whose family is baptized with him after helping Peter. But few realize that Acts 16, sandwiched between references to Lydia, is Dez, the jailer of Philippi, whose family is baptized with him after helping Psaul.

A lot of Christians overlook these facts because most Christians have lost touch with military families like Lydia’s. But military families often cannot help but notice. The question is whether most Christians will choose to look at their blindspots or continue to ignore them. And military families.