When "Lament" is Liturgical Theater

I've been sitting with something that makes my skin crawl.

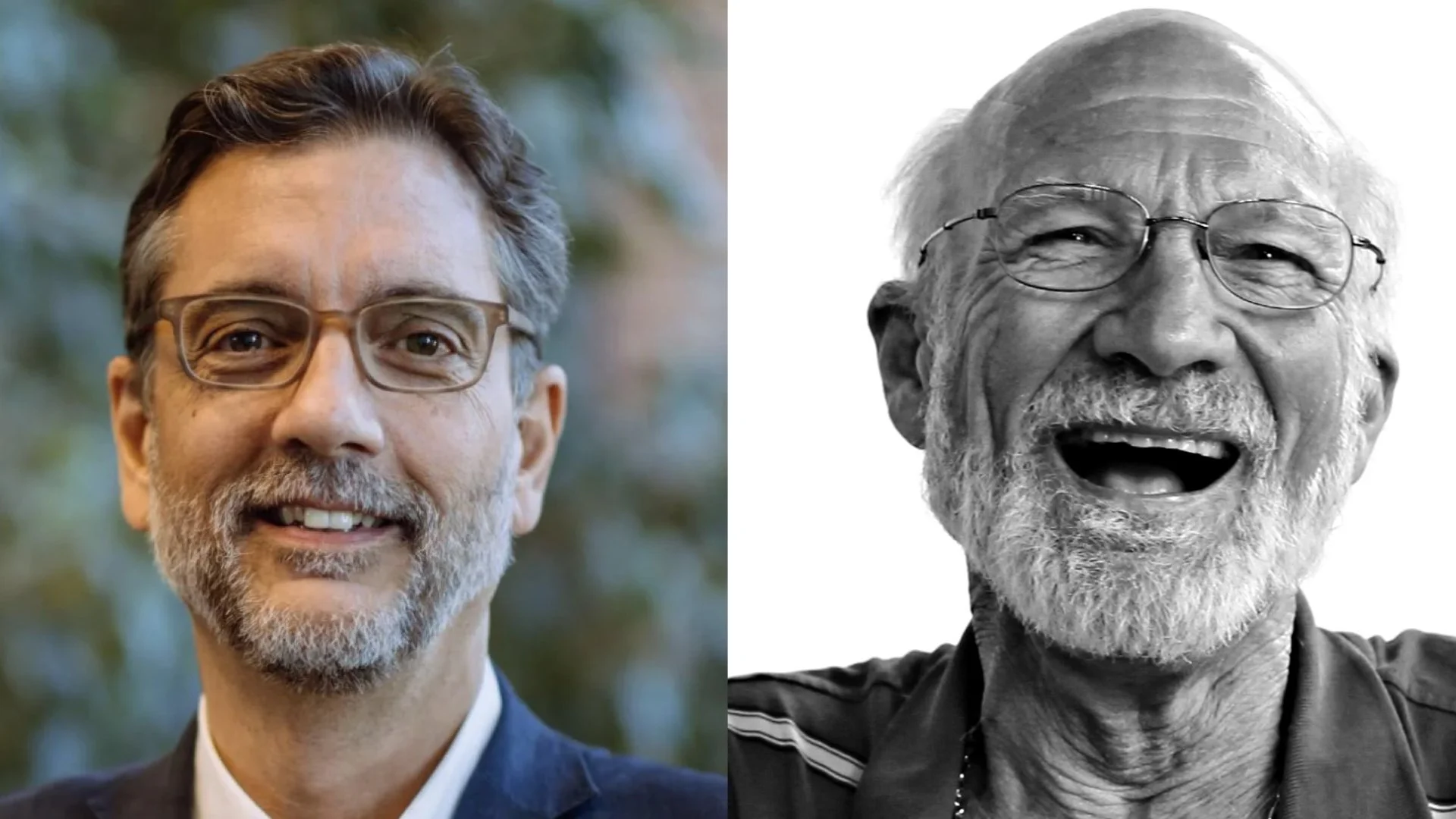

In October 2011, I interviewed Stanley Hauerwas at Duke. We talked about moral injury, about the church's complicity in sending people to war without adequate formation, about Veterans Day pageantry and the people who "put on their little hats" despite never having killed anyone.

And then Stanley said this:

"I think the church has failed miserably... we need to express and confess our complicity in the destruction of people for not preparing adequately them to understand that we Christians have a problem with war."

Fast forward to 2024. George Kalantzis—who counts Hauerwas among his intellectual influences—sits across from me on Grunt God and says:

"What I want to propose is that actually for families, we should have services of lament and repentance—not for them to repent and lament—but our complicity that makes it necessary for their children to be at war."

Fourteen years. The same diagnosis. The same prescription. The same hollow performance.

The Pattern

I don't know if George and Stanley ever discussed this specific formulation. Maybe they did, maybe they didn't. But it doesn't matter. What matters is that this prescription—"services of lament for our complicity"—has been the go-to move of progressive Christian intellectuals for at least fourteen years, probably longer.

And in those fourteen years, what has changed?

The academy still determines whose voice counts as "theological." Veterans are still invited to share our trauma as object lessons in just war seminars, but not to teach the seminars. We're still the raw material for civilian theological production, not the producers.

TYFYS in Vestments

Here's what I've come to understand: "We need to lament our complicity" is just "Thank You For Your Service" in church clothes.

Both are performative gestures that:

Acknowledge a debt without paying it

Express concern without accepting consequences

Maintain the speaker's moral position without disrupting their material position

Treat veterans as objects of pastoral care rather than subjects of our own theological authority

When someone says "thank you for your service" in the grocery store, I know what they're doing: purchasing moral comfort for the price of three words. They get to feel grateful without examining why they're not the ones who served. The transaction is complete. I'm supposed to say "you're welcome" and we both move on.

When a theologian says "we need to lament our complicity," the same transaction is happening—just with more syllables and better footnotes. They get to feel morally serious without examining why they're still the ones with tenure. The liturgy is performed. We're supposed to feel heard. Everyone moves on.

Except we're still stuck with the nightmares. Still fighting the VA. Still excluded from the theological conversations about the wars we actually fought. Moving on is a luxury, a privilege. It's Entitlement Religion.

Entitlement Religion feeds Toxic Pacifism while watching pacifists starve.

The "Confession" That Isn't

The Greek word for confession is homologia (ὁμολογία)—literally "same word" or "same speech." True confession creates shared speech, restored language between the confessor and the oppressed. It's supposed to produce change because it produces proximity.

But look at what this liturgical prescription produces: distance.

Stanley confesses Duke's complicity from his position at Duke. George confesses the church's complicity while recommending everyone read theologians who've never worn the uniform. They both say we need to "listen" to veterans—but listening still positions them as the authorized listeners and us as the therapeutic objects of their pastoral attention.

Real confession would mean: "I'm going to step aside so you can have a seat at the Table too." Real lament would mean: "I'm going to stop writing about military ethics until I earn the right from military communities." Real repentance would mean structural change, not liturgical performance.

Instead, we get fourteen years (at minimum) of the same beautifully worded acknowledgment that functions as a substitute for actual progress.

Why It Persists

This pattern persists because it serves the dominant class perfectly.

The civilian gets to:

Appear morally serious and prophetically critical

Maintain their social position and cultural authority

Control the theological discourse about war

Feel absolved of complicity through the cheap act of naming it

Meanwhile, the veteran gets:

Acknowledged as wounded (but not as authoritative)

Invited to testify (but not to interpret)

Offered pastoral care (but not institutional power)

Positioned as object of theology (but not as its subject)

It's brilliant, really. By naming complicity, Entitlement Religion immunizes itself against the charge of complicity. "Confession" becomes the substitute for conversion.

The Cost

In the 2011 interview, Stanley told me: "I think people are damaged by that, even if they haven't killed anyone. I think the very fact that they have to envision the possibility that they kill someone is not something that any of us know how to envision as an ongoing way of life."

He's right. We are damaged.

But here's what he didn't say—and what George didn't say either: You don't get to diagnose our damage without examining your role in producing it.

The intellectual class that sends us to war with inadequate theological formation is the same class that excludes us from theological education when we return. The same people who lament our "moral injury" are the same people who maintain the credentialing systems that ensure we can't become the ones doing the diagnosing.

The complicity isn't just in what the church failed to tell us before we deployed. The complicity is in what the church refuses to let us say after we return.

What Would Real Lament Look Like?

I'll tell you what it wouldn't look like: another service, another symposium, another essay in a journal that regular veterans can't access without institutional affiliation.

Real lament would mean:

Veterans teaching the just war theory courses

Veterans with lived theological authority, not just therapeutic testimony

Academic positions for people whose "doctoral" work was done in the moral wilderness of combat

Seminaries structured around our questions, not questions about us

Real lament would mean Stanley and George and every other civilian theologian who's built a career interpreting military experience saying: "We've been doing this wrong. Here's the platform. Here's the authority. Here's the institutional access. What do YOU have to say?"

But that would require them to believe their own diagnosis of complicity. And if they believed it, they'd have to stop being complicit. And if they stopped being complicit, they'd lose the authority to offer absolution for complicity. The truth is, they don't really believe what they say they believe, they're just speech-actors. Or, as I worded it to George in his own 🇬🇷 native tongue,

this is not simply about me. It is about your public witness and the ἐκκλησίαν [ekklesia] it assumes, whether your words to me were truthful or merely a performance, a δρᾶμα [drâmă].

The whole system depends on the performance continuing, on people like Hauerwas and Kalantzis continuing to be hypokritēs. Pretenders, not believers.

Fourteen Years and Counting

So here we are. 2025. Same prescription. Different voice.

How long before another well-meaning civilian theologian, inspired by Hauerwas or Kalantzis, offers the same liturgical solution to the same structural problem?

How many more decades of confessing complicity without ending it?

How many more services of lament that function as substitutes for justice?

How long will Christians accept performance as substitute for repentance?