GruntGod 2.4.1: What's in a Name?

Why Your Bible Hides the Most Important Word in the Gospels

If I told you the most important word in the New Testament is hidden in plain sight, you'd probably assume I was going to pull out some Greek word and make you feel bad for not knowing it. I am, but not the one you think.

The word is Iēsous (G2424), and the problem isn't that you don't know it — it's that you know it too well. You say it all the time. You just don't know what it means, because in English it doesn't mean anything.

"Jesus" is linguistic filler.

Here's how we got here. Mary and Joseph spoke Aramaic on the streets and Hebrew in the synagogue. When the angel told Mary to name her boy, the name was Yᵊhôšûa (H3091) — Joshua. "God is salvation." When the Greek-speaking evangelists wrote it down decades later, they transliterated it as Iēsous, which is about as meaningful in Greek as "Jesus" is in English. The sound survived; the meaning didn't.

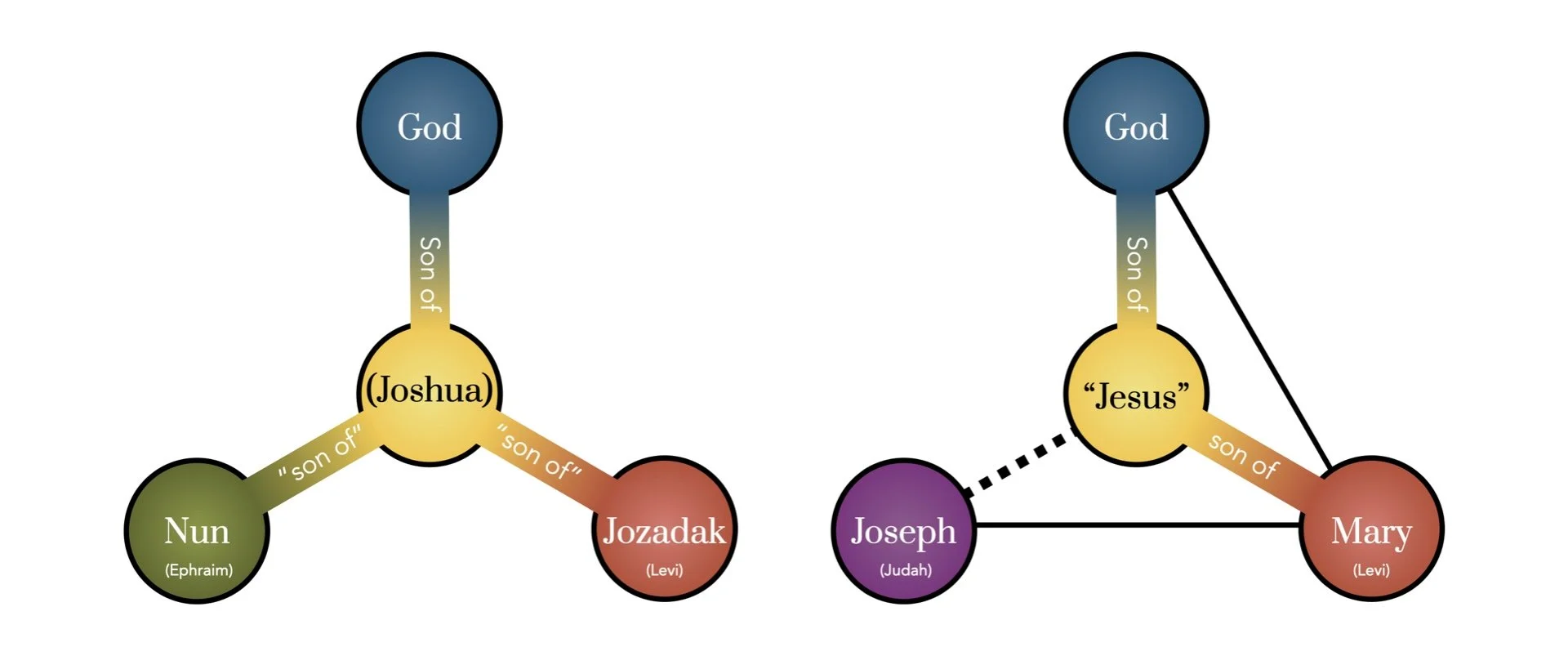

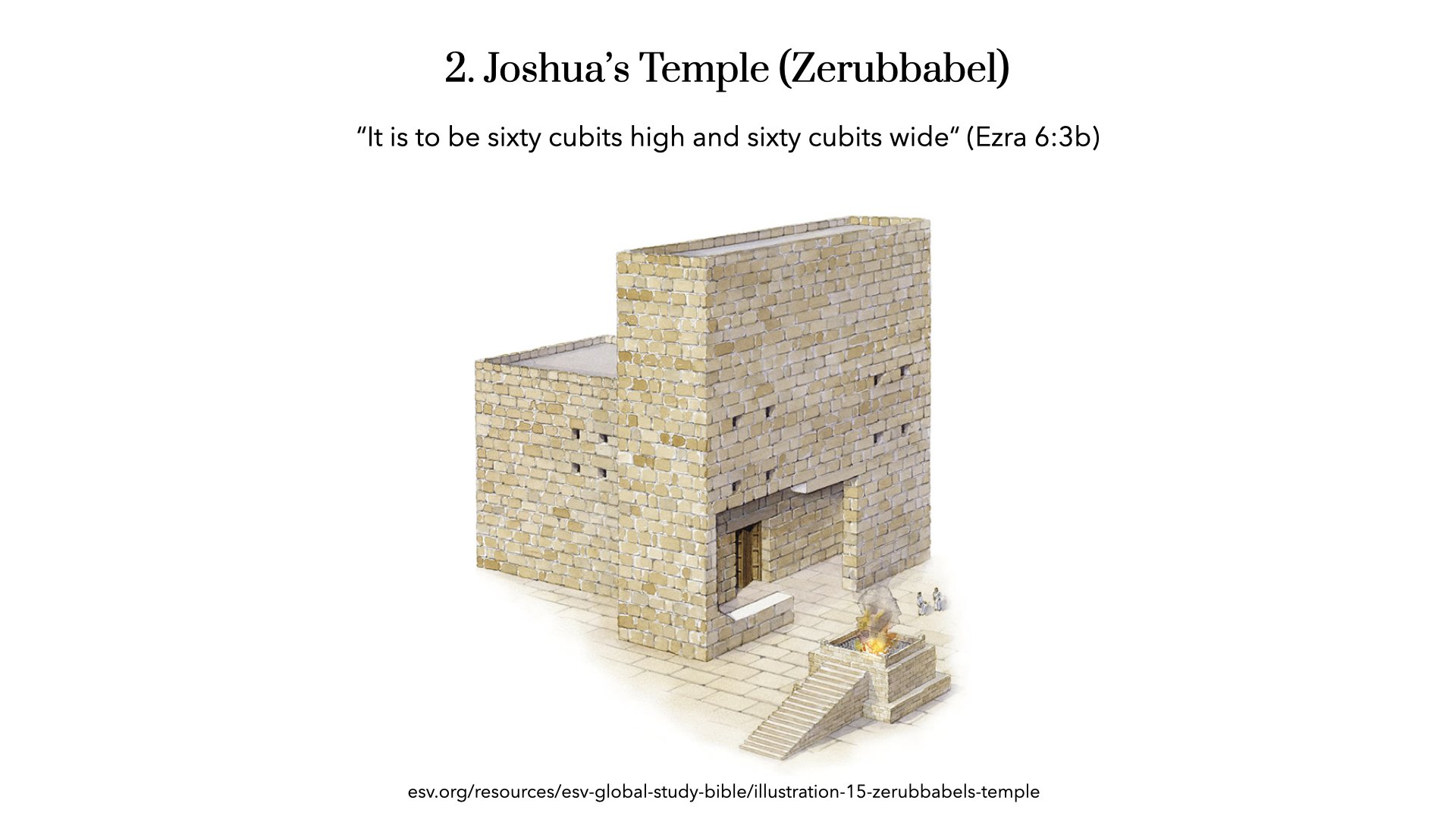

This matters because Christ's name isn't arbitrary — it's loaded. It points directly to two Old Testament figures. The first Joshua, son of Nun, was Moses' executive officer who led God's people in combat to take the Promised Land. The second Joshua, son of Jozadak, was the first high priest after the Babylonian exile who "set out to rebuild the house of God in Jerusalem" (Ezra 5:2). The NRSV translates this second Joshua as "Jeshua" because the relevant section of Ezra was written in Aramaic — the same Aramaic Mary and Joseph spoke at home.

Soldier and priest. Combat leader and temple builder. Two men, one name, and a newborn destined to fulfill both roles.

The diagrams I built for the chapter revision make this clearer than I can in a blog post, but here's the short version: both Old Testament Joshuas were "sons of" someone (bēn, H1121) and both served as "ministers" (šāraṯ) of God. One ministered through military service, the other through priestly service. When a messenger tells Mary to name her son Joshua — the son of both God and a descendant of David's royal line — every Bible-thumping Jew in earshot would have heard the echo.

John makes the connection explicit with his phrase "the temple of his body" (John 2:21). This is not a generic metaphor. The temple standing in Jerusalem when Jesus walked through it was Joshua's temple — built by Jozadak's kid after the exile. When John says Jesus' body is the temple, he's saying Joshua built the temple again, this time in flesh.

The next time someone tells you to "say his name," try saying the one his mother actually used. When you say Joshua, you're not just naming a historical figure — you're making a confession. You're saying God is salvation. That's not a sound; that's a creed.

This post draws on material revised out of the second edition of God Is a Grunt. The book version streamlines this argument for military families; the linguistic detail lives here for those who want the receipts.