GruntGod 2.3.5: Rules of Engagement

Why R.O.E. Protect the Protectors

This post draws on exegetical material from my revised chapter on Joshua for the second edition of God Is a Grunt.

What happens when one soldier loots?

It's not a hypothetical question. Military history is full of answers, from the sack of Rome to the rape of Nanking to Abu Ghraib. When discipline breaks down and soldiers start taking liberties, the moral corruption spreads. Individual violations become unit culture. Unit culture becomes institutional failure.

But we tend to think of rules of engagement (ROE) primarily as protecting noncombatants. Don't harm civilians. Don't target protected sites. Don't use excessive force. These are crucial protections, and violations should be prosecuted. But they're not the primary reason ROE exist.

In 2008 I testified on the Rules of Engagement panel for Winter Soldier: Iraq and Afghanistan.

Rules of engagement exist to protect the warriors themselves from moral corruption.

The book of Joshua makes this startlingly clear.

The Achan Incident

After the walls of Jericho come tumbling down, Joshua issues explicit orders: "Keep [šāmar] yourselves from the things devoted [ḥāram, v.] to destruction [ḥērem, n.], lest they make the camp [maḥănê, H4264] of Israel a thing for destruction [ḥērem]" (Josh. 6:18 ESV).

The language is precise. Don't just avoid taking the devoted things. Guard yourselves against them. The Hebrew šāmar means "to keep," "to guard," "to protect." It's an active verb requiring vigilance and self-discipline.

Why? Because touching the ḥērem makes you ḥērem. The devoted thing is spiritually toxic. If you take it for yourself, you become what you were supposed to destroy. It consumes you because evil is like a parasite.

One soldier doesn't listen. Achan sees some silver, gold, and a fancy cloak in the rubble of Jericho. He takes them and hides them in his tent. Nobody knows. Nobody sees. It's a victimless crime, right? Just some war loot that would've been destroyed anyway.

Wrong.

The next battle, against the much smaller city of Ai, is a disaster. Israel loses. Men die. The text says God's anger burns against Israel because of Achan's theft. The corruption of one soldier has made the entire maḥănê liable for divine judgment.

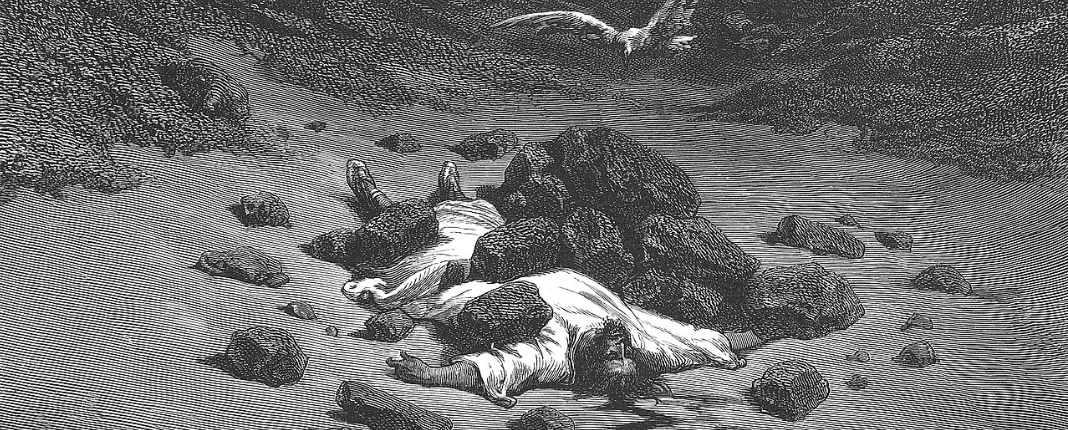

When the theft is discovered—through divine revelation via casting lots—Achan is stoned to death. His family is stoned with him. Their bodies are burned. Their possessions are destroyed. A pile of stones marks the spot "to this day" (Josh. 7:26).

Detail from The Stoning of Achan by Gustav Doré.

The brutality is shocking. But the logic is clear: individual corruption pollutes the whole community. When one protector violates the rules, everyone suffers the consequences.

Camp, Host, Company, Army

The Hebrew word maḥănê is crucial here. It can be translated as "camp," "host," "company," or "army." English translations have to choose, but the Hebrew doesn't distinguish between military and civilian populations. Maḥănê refers to the whole assembly—everyone who's part of Israel, whether they fight or not.

This matters because it means Achan's theft doesn't just endanger the fighting men. It endangers the entire community. The moral pollution spreads. The spiritual toxicity contaminates everyone.

When Joshua warns that one person's violation can "make the camp of Israel a thing for destruction," he's not using metaphor. He means it literally. The ḥērem is contagious. Touch it wrong, and you become it. And once one person is infected, the whole maḥănê is at risk.

That's why Achan and his family have to be destroyed. Not as punishment exactly—though it is that—but as quarantine. The corruption has to be cut out before it spreads further. Rather than the whole maḥănê being devoted to destruction, Achan's household absorbs the judgment.

It's horrifying. It should be. But it reveals something we desperately need to recover: one person's betrayal corrupts the whole organization.

The Blue Falcon Principle

In military slang, a "blue falcon" is a buddy fucker—someone who betrays their battle buddies for personal gain. Achan is the archetypal blue falcon. He loots for himself while pretending to follow orders. He puts his personal greed above the mission. He violates the trust of his unit.

And everyone pays.

The blue falcon principle applies beyond Jericho. Every unit knows someone who's willing to throw others under the bus to save themselves. Every organization has people who violate policy when they think nobody's watching. Every community has folks who betray collective commitments for individual advantage.

James Manning dipped into the KKK playbook to keep civil rights from fellow military families, an excellent example of a blue falcon.

We tend to treat these as isolated incidents. "One bad apple." "Don't judge the whole unit." "Keep things in perspective." But Joshua won't let us compartmentalize. The text insists that one person's corruption makes the whole maḥănê liable.

This isn't ancient superstition. It's moral reality. When one cop brutalizes someone in custody and the force rallies to protect him, the whole department becomes complicit. When one soldier commits a war crime and the unit covers it up, everyone shares the guilt. When institutional corruption gets exposed and leadership stonewalls accountability, the entire organization loses legitimacy.

The moral pollution spreads. The blue falcon infects the whole formation.

Why ROE Protect the Protectors

Rules of engagement are designed to prevent this. Not primarily by protecting civilians—though they do that—but by protecting soldiers from becoming "warriors;" the kind of people who violate just limits on violence.

Joshua's warning is explicit: touch the ḥērem wrong, and you become ḥērem. Violate the rules, and you corrupt yourself spiritually and morally. Take what's devoted to God, and you'll be devoted right alongside it.

This is why ROE violations can't be swept under the rug. Why covering for blue falcons is itself a form of corruption. Why "what happens on deployment stays on deployment" is a recipe for moral disaster.

The rules don't just constrain behavior. They protect character. They guard against the transformation of servant-protectors into predators and looters. They maintain the boundary between justified containment and unjustifiable violence.

When we shrug off ROE violations—when we say "war is hell" or "civilians don't understand" or "that's just how it is"—we're Achan hiding silver in our tent. We're pretending individual corruption doesn't poison the whole maḥănê. We're ignoring Joshua's explicit warning.

And we'll lose the next battle. Not because God is smiting us, but because moral corruption undermines tactical effectiveness. Units that tolerate blue falcons lose cohesion. Organizations that cover for institutional failure lose legitimacy. Communities that shrug off brutality lose the moral authority necessary for maintaining order.

The Achan Question

Every military family knows an Achan story. Maybe it's the NCO who fragged his lieutenant. Maybe it's the cop who planted evidence. Maybe it's the commander who covered up the scandal. Maybe it's you, hiding something you took when you thought nobody would know.

The question Joshua poses: Are you going to šāmar yourselves from the ḥērem? Are you going to guard against moral corruption with the same vigilance you'd use against physical threats?

Or are you going to shrug it off, minimize it, cover for it, pretend one person's failure doesn't affect everyone?

Because the text is clear: it does. One soldier's theft cost lives at Ai. One person's corruption endangered the whole camp. The rules of engagement exist not primarily to protect the enemy but to protect you from becoming something you can't come back from.

Touch the ḥērem wrong, and you become ḥērem. Violate the rules, and you corrupt the entire maḥănê. The blue falcon doesn't just betray their buddies. They infect the whole formation.

Joshua knew this. That's why the punishment was so severe. That's why the warning was so explicit. That's why the rules couldn't be bent or excused or explained away.

The same applies today. When we say "to serve and protect," we're claiming the āḇaḏ and šāmar mandate from Genesis 2:15. When we violate that mandate—when we brutalize instead of protect, when we corrupt instead of serve—we make ourselves ḥērem.

And we take everyone down with us.

Logan M. Isaac served as an artillery forward observer in Iraq and trained in virtue ethics under Stanley Hauerwas at Duke. His second edition of God Is a Grunt uses hagiographic methodology to teach virtue ethics through military biography. Subscribe for more content wrestling with military ethics and biblical theology.