GruntGod 2.3.4: Ḥāram and Holy Warv

What Joshua Teaches About Violence

This post draws on exegetical material from my revised chapter on Joshua for the second edition of God Is a Grunt.

Let's be clear from the start: Joshua describes genocide.

Not metaphorical spiritual warfare. Not hyperbolic ancient rhetoric that we can safely domesticate. The text explicitly commands the destruction of entire populations—men, women, children, livestock. The Hebrew verb ḥāram (H2763) means "to reserve entirely to God by destruction." The noun ḥērem (H2764) refers to the thing or person devoted to destruction.

This is divinely commanded ethnic cleansing. There's no way around that. We shouldn't try.

But here's what's weird: the more carefully you read Joshua, the less it seems designed to justify violence and the more it seems designed to warn against it. By ignoring or downplaying this text, we will miss that warning. In doing so, we diss/miss those for whom these events are not just Biblical, but personal. That's civilian bias avoiding civilian privilege, reinforcing the toxic pacifism of civilian theology.

The Basketball Ball Problem

If ḥāram and ḥērem feel familiar, they should. The same verbal/nominal pattern appears with pesaḥ (H6453)—Passover. The word names both the ritual and the victim. Saying "Passover sacrifice" is like saying "basketball ball." The action and its object share the same root.

This matters because it reveals how the Hebrew conceives of devoted things. They're not simply objects of violence. They're liturgical categories. The devoted thing becomes ḥērem through the act of ḥāram—through being set apart, reserved entirely for God.

Only in Joshua, the devoted things are human beings, not calves.

That liturgical framing doesn't sanitize the violence. If anything, it makes it more disturbing. This isn't random chaos or individual bloodlust. It's ritualized, commanded, systematized destruction. The kind of violence that requires organization and communal participation, not just individual brutality.

What's a little (human) sacrifice between adversaries in the Military Industrial Culture Wars?

Why God Had to Command It

Here's where the text gets even more uncomfortable. God doesn't just permit Israel to take the land by force. God commands it. And the text tells us why: because the first time Israel was supposed to take the land, they refused (Numbers 13-14).

The recon scouts reported that the land "devours its inhabitants; and all the people that we saw in it are of great size" (Num. 13:32). Faced with what appeared to be an impossible task, most of Israel lost faith. They cowered in fear and started talking about returning to slavery in Egypt.

Only Joshua and Caleb held firm: "The LORD is with us; do not fear them" (Num. 14:9). But fear won the day, and Israel wandered in the wilderness for another generation.

So when Israel finally does enter the land, God doesn't leave it to their initiative. God commands the violence. God has to, because Israel already proved they'll get gun-shy when the mission looks hard, when it may cost a little blood, sweat, and tears.

This doesn't justify the violence theologically. But it does complicate the Sunday school version where God is an angry deity who likes smiting people. The text suggests God commands ḥāram not because God delights in destruction but because God's people can't be trusted to do what's necessary without explicit divine authorization.

What Joshua Actually Emphasizes

Here's what makes Joshua so strange as a conquest narrative: most of the book isn't about conquest.

Less than a quarter of Joshua describes expelling Canaanite inhabitants with violent force. Chapters 6-11 contain the military campaigns, but even within those chapters, there's substantial material about peaceful negotiations. Chapter 13 explicitly states that the victory was not total—plenty of Canaanite populations remained.

Most scholars agree that the language of violent conquest is exaggerated and self-congratulatory, which is par for the course in ancient Near Eastern literature. Every king claimed total victory. Every campaign was described as annihilating the enemy. These are literary conventions, not historical reportage.

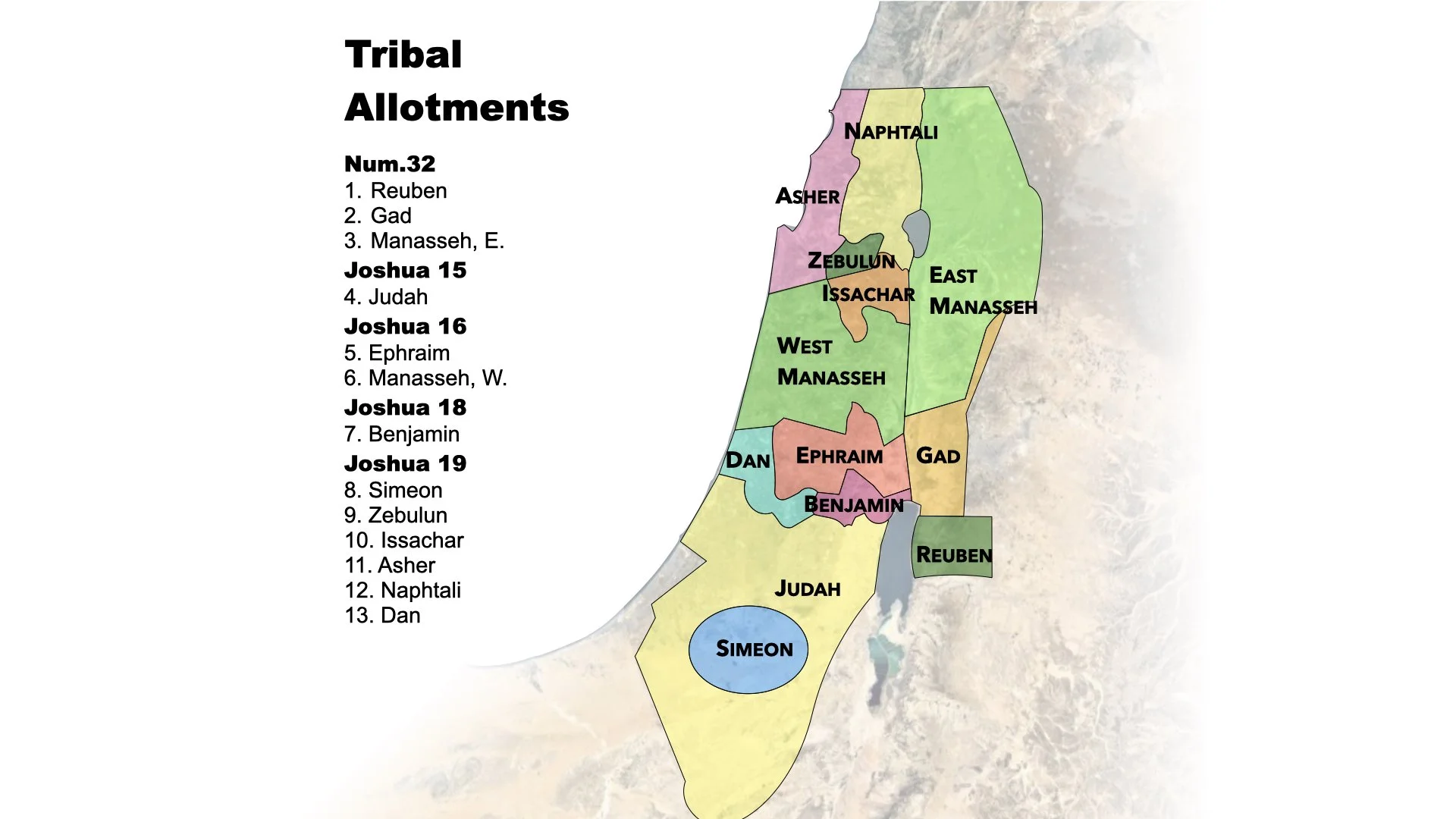

But even more telling: ten chapters—13 through 22—outline in painstaking detail how the Promised Land will be allocated to the tribes according to their size. The emphasis is on fairness, organization, and just distribution of resources. Battle is not the main story of Joshua. It's a prelude to the real mission: establishing a well-ordered community.

Rules of Engagement

The text's treatment of ḥāram itself undermines any simple glorification of violence. Joshua warns the people to "keep [šāmar] yourselves from the things devoted [ḥāram, v.] to destruction [ḥērem, n.], lest they make the camp [maḥănê, H4264] of Israel a thing for destruction [ḥērem]" (Josh. 6:18 ESV).

Two points are crucial here. First, rules of engagement don't just protect noncombatants. They protect the warriors themselves from corruption and evil. Don't take the ḥērem for yourselves, or you'll become ḥērem. The devoted thing is spiritually toxic—it corrupts those who touch it.

Second, individual violation pollutes the whole community. The Hebrew word maḥănê doesn't distinguish between soldier and civilian. It can mean "camp," "host," "company," or "army." Here it refers to all of Israel, not just the fighting men. If one person betrays the ḥāram command, the whole maḥănê becomes liable for destruction.

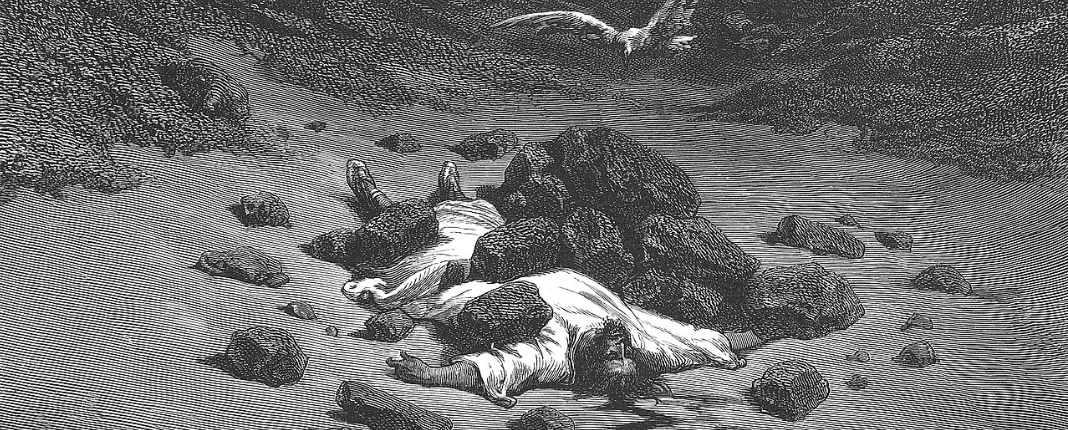

This isn't theoretical. After Jericho, Israel suffers a devastating loss at Ai because one soldier—Achan—looted some silver and gold. When his theft is discovered, Achan is stoned to death and his family burned alive. The text doesn't flinch from the brutality.

Detail from The Stoning of Achan by Gustav Doré.

The logic: Achan's individual corruption made the entire assembly liable. Rather than all Israel being devoted to destruction, Achan and his household absorb the judgment. When one protector abuses their power, the whole community becomes morally polluted.

Not a Manual, a Warning

Joshua doesn't work as a manual for holy war. The rules of engagement change almost every battle. When people try to take things into their own hands, they lose. The conquest of Jericho involves a parade formation that must have been the laughingstock of the city—priests, musicians, and a slow march around the walls. This isn't strategy. It's liturgy.

Nowhere does Joshua make command decisions. There's an imposing figure who identifies himself as "the commander of the army of the LORD" (Josh. 5:14). Joshua knows he's outranked. Humans aren't in charge here.

So what is Joshua teaching?

Maybe this: violence, even divinely commanded violence, is deeply dangerous. It corrupts those who enact it unless they maintain strict discipline and collective accountability. The devoted things are toxic. Touch them wrong, and you become what you're trying to destroy.

Maybe this: the point of military force isn't conquest but order. The emphasis throughout Joshua is on organization, fair distribution, and maintaining communal integrity. The violence is horrifying, but it's also contained—limited by strict ROE, punished when violated, and ultimately subordinated to the larger mission of establishing justice.

Maybe this: we can't dodge the horror by claiming "that's the Old Testament" or "those were different times." Joshua forces us to reckon with divinely sanctioned violence. Not because we're supposed to imitate it, but because we're supposed to learn from Israel's failure to maintain moral discipline even under direct divine command.

If Israel, with God speaking audibly and commanding explicitly, still produced blue falcons like Achan who corrupted the whole camp—what hope do we have?

That's the question Joshua leaves us with. Not "How do we justify holy war?" but "How do we maintain moral integrity when violence becomes necessary?"

I don't have a clean answer. Neither does Joshua. But the text won't let us pretend the question doesn't exist. So let's stop pretending and start working to build better theologies that don't avoid the hard work before us.

Logan M. Isaac served as an artillery forward observer in Iraq and trained in virtue ethics under Stanley Hauerwas at Duke. His second edition of God Is a Grunt uses hagiographic methodology to teach virtue ethics through military biography. Subscribe for more content wrestling with military ethics and biblical theology.