GruntGod 2.1.1: From Printing Press to PTSD

The Etymology of "Stereotype"

I'm deep in revisions for the second edition of God Is a Grunt, systematically working through each chapter to sharpen the hagiographic method while keeping the book accessible to military families. The Cain chapter examines moral pain and the "All Soldiers Kill" (ASK) stereotype that damages both combat veterans and those who never pulled a trigger. While cutting technical material to maintain primary audience focus, I realized the etymology of "stereotype" itself is too good to leave out entirely.

Metal Cubes and Permanent Casting

The word "stereotype" comes from 19th-century printing technology. Before mass production, creating a book was painstaking labor. Individual letters on small metal cubes had to be placed one by one in rows on a wooden shelflike contraption called a "chase," which would be slathered in ink and pressed to paper to create one side of a page. Hundreds of chases were used to create copies of books, and then they were deconstructed when printing was done. If publishers underestimated a book's demand, then each chase would have to be typeset all over again—letter by letter, line by line, page by page.

Photo by Hannes Wolf / Unsplash

Stereotyping solved this problem by making a more permanent way to ink pages in mass quantities. Instead of chases being made up of metal cubes representing individual letters, the whole page was cast as a single piece of metal. Publishers could store stereotype plates and reprint popular books without the headache of reconstruction.

This convenience came at a cost: no changes could be made after the stereotype was cast. Want to fix a typo? Tough luck. Update outdated information? Start over. The word "stereotype" came to mean something repeated over and over again, from stereos (G4731), a Greek word meaning "fixed or unchanging."

From Printing to Psychology

By the early 20th century, journalist Walter Lippmann borrowed the printing term for social psychology. In his 1922 book Public Opinion, Lippmann argued that people use mental shortcuts—stereotypes—to make sense of complex social reality. We don't have time to carefully evaluate every person and situation we encounter, so we categorize. These categories aren't necessarily accurate, but they're efficient.

Lippmann was describing a cognitive process, not making a moral judgment. But by mid-century, "stereotype" had acquired its negative connotation. Gordon Allport's 1954 The Nature of Prejudice connected stereotyping to discrimination and dehumanization. Stereotypes, Allport argued, allowed people to justify mistreatment of entire groups by reducing individuals to caricatures.

Christianity Today thought it was okay to pathologize veterans for clicks.

The printing metaphor fits perfectly: stereotypes are fixed, unchanging, repeated without revision. Like stereotype plates that can't be edited, social stereotypes resist correction even when confronted with contradictory evidence. Tell someone their assumption is wrong about this particular veteran, and they'll file it as an exception while maintaining the rule about veterans in general.

Military Stereotypes Are Fixed Plates

When Vietnam veterans came home, America cast them in the stereotype of Villain. Baby-killers. Drug addicts. Ticking time bombs. Never mind that most were drafted against their will. Never mind that the vast majority never committed atrocities. The stereotype was cast, and it repeated through media, politics, and popular culture for an entire generation.

Then came 9/11 and the Iraq/Afghanistan wars. Collective guilt over Vietnam produced overcorrection: now military service is uniformly heroic. But the new stereotype—Victim—is just as dehumanizing. War-torn. Traumatized. Broken. Soul-scarred. Thank you for your sacrifice.

Stereotypes are fixed plates that refuse to accommodate reality. Vietnam veterans who served honorably. Iraq veterans who aren't traumatized. Afghanistan veterans who regret enlisting for economic reasons but don't regret their service. Fobbits and REMFs who never left the wire but still deal with combat stress. Air Force personnel who feel their experience "doesn't count" compared to Army infantrymen.

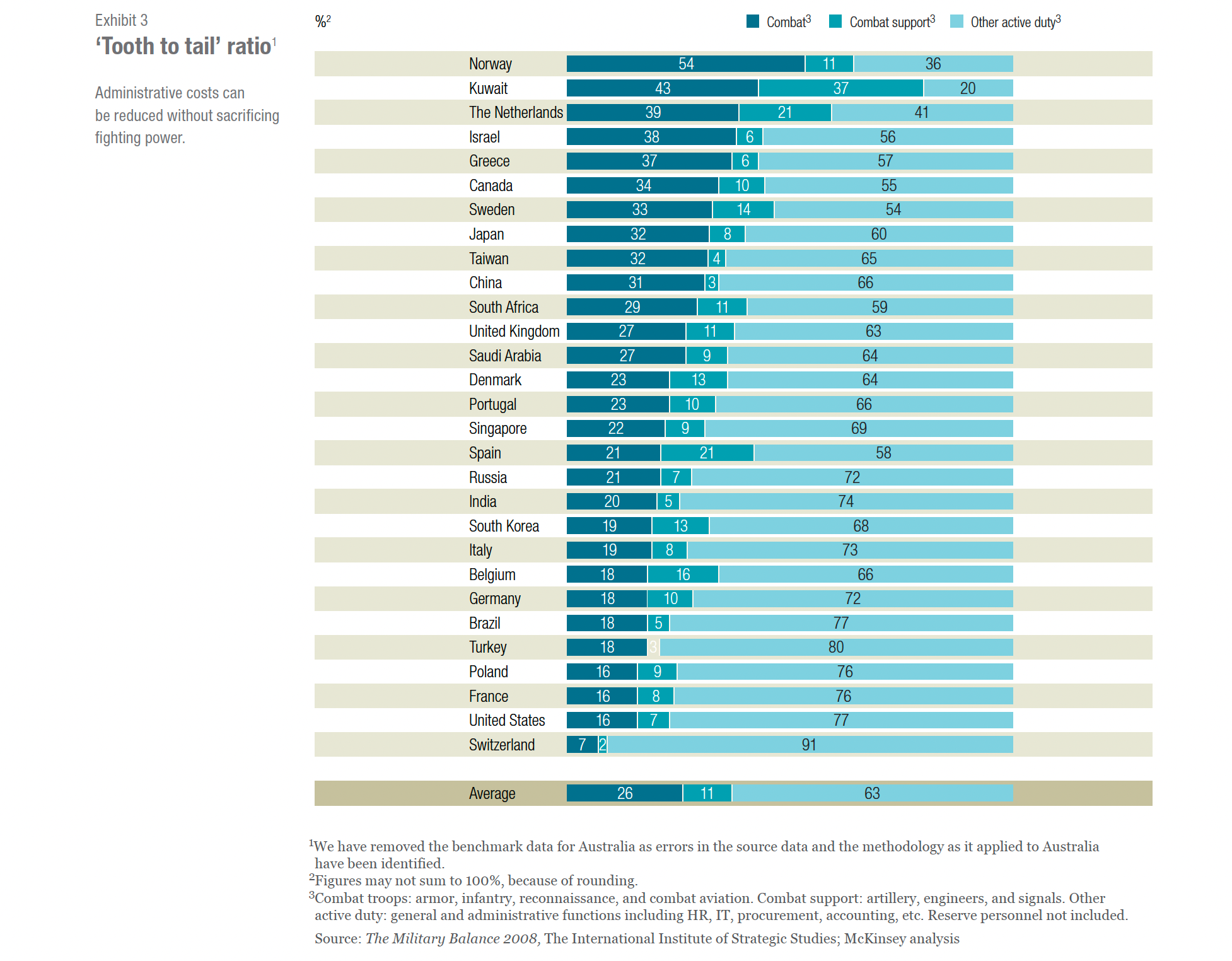

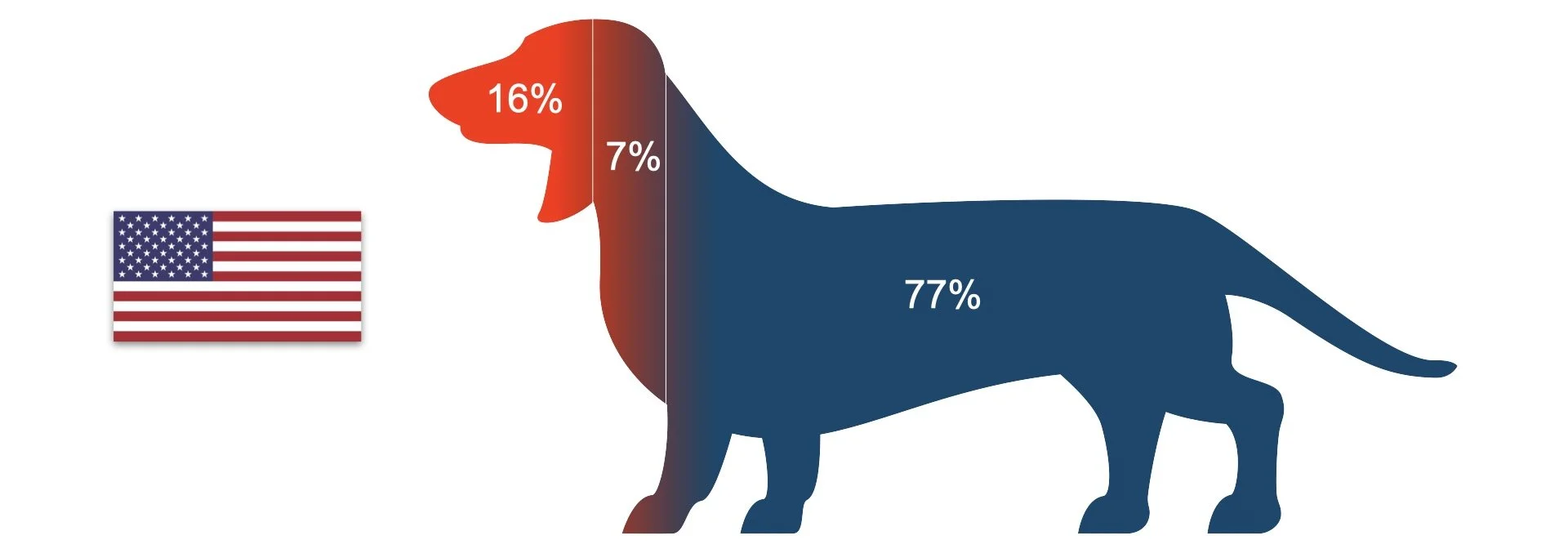

The ASK stereotype—All Soldiers Kill—compounds this problem by reducing military service to its most dramatic element. According to 2010 data from thirty developed nations, the global average Tooth to Tail ratio is 63% support personnel to 37% combat arms. For the United States, it's 77% Tail. Three-quarters of service members are in non-combat roles. But ask civilians what soldiers do, and they'll describe kicking in doors and calling in airstrikes.

Breaking the Plate

Here's what makes stereotypes particularly insidious: repetition creates truth. Say something enough times, especially through authoritative sources (government, media, churches), and people believe it regardless of evidence. The psychiatric profession stereotyped tempestuous women as hysterical. Missionaries stereotyped Native Americans as savages. Social workers stereotyped poor mothers as welfare queens. Christians stereotype combat veterans as war-torn.

These aren't innocent simplifications. They're tools of social control that benefit those who deploy them. Thank You For Your Service isn't about veterans—it's about civilians performing gratitude to discharge their guilt over wars they voted for, taxes they paid, and suffering they caused but didn't experience.

Breaking stereotypes requires two things: counterstories (narratives that complicate simplistic categories) and exposure of how stereotypes serve those who hold them more than those they depict.

The Cain chapter in God Is a Grunt attempts both. It offers a counterstory—Cain as the Bible's prototype for confession rather than the devil's seed—and exposes how the ASK stereotype serves civilian interests (confirming their assumptions, allowing morbid curiosity, performing gratitude) while harming military communities (inadequacy, shame, suicide).

Stereotypes are fixed and unchanging, but human beings aren't. Recognizing a pattern isn't the same as understanding a person. If you want to know what someone has experienced, ask them—not your precast assumptions about their demographic category.

This post draws from material cut during revision of the Cain chapter in "God Is a Grunt" (2nd edition), which examines moral pain and the "All Soldiers Kill" stereotype through the hagiographic lens of Genesis 4.