The Martyrdom of Ralph Abernathy

*This essay has been crossposted at GIJustice.com/blog/martyrdom-ralph-abernathy

Every January, America performs its annual ritual of King veneration. We quote the Dream speech, invoke the arc of justice, and maintain the careful fiction that Martin Luther King Jr. was something other than human. We have built a civil religion around his memory, complete with temples, feast days, and an elaborate priesthood tasked with protecting the saint from any whiff of the profane.

Ralph David Abernathy committed heresy against this religion, and he was punished accordingly.

In October 1989, Abernathy published his memoir "And the Walls Came Tumbling Down." The book revealed what those close to King already knew: that King was a man of appetites and contradictions, capable of extraordinary courage and ordinary failings in equal measure. Abernathy, King's closest friend and constant companion through the movement, refused to wash the humanity from the icon.

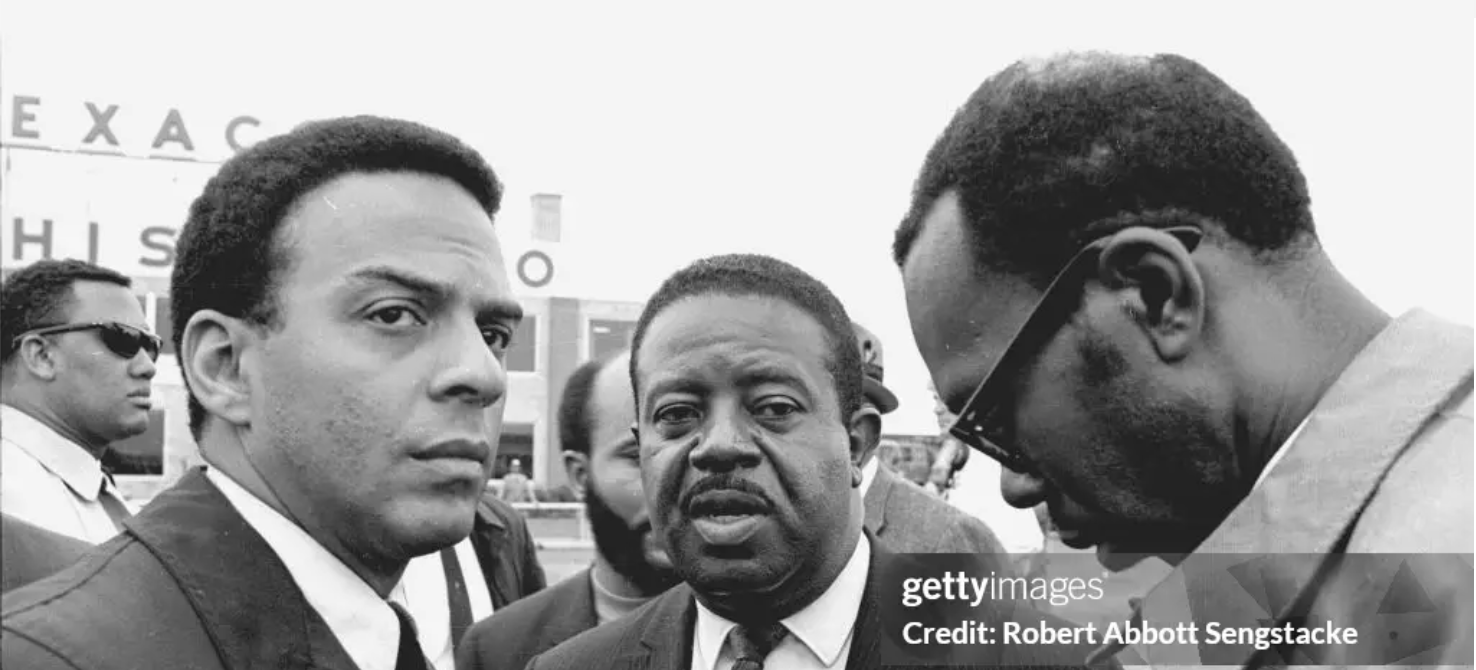

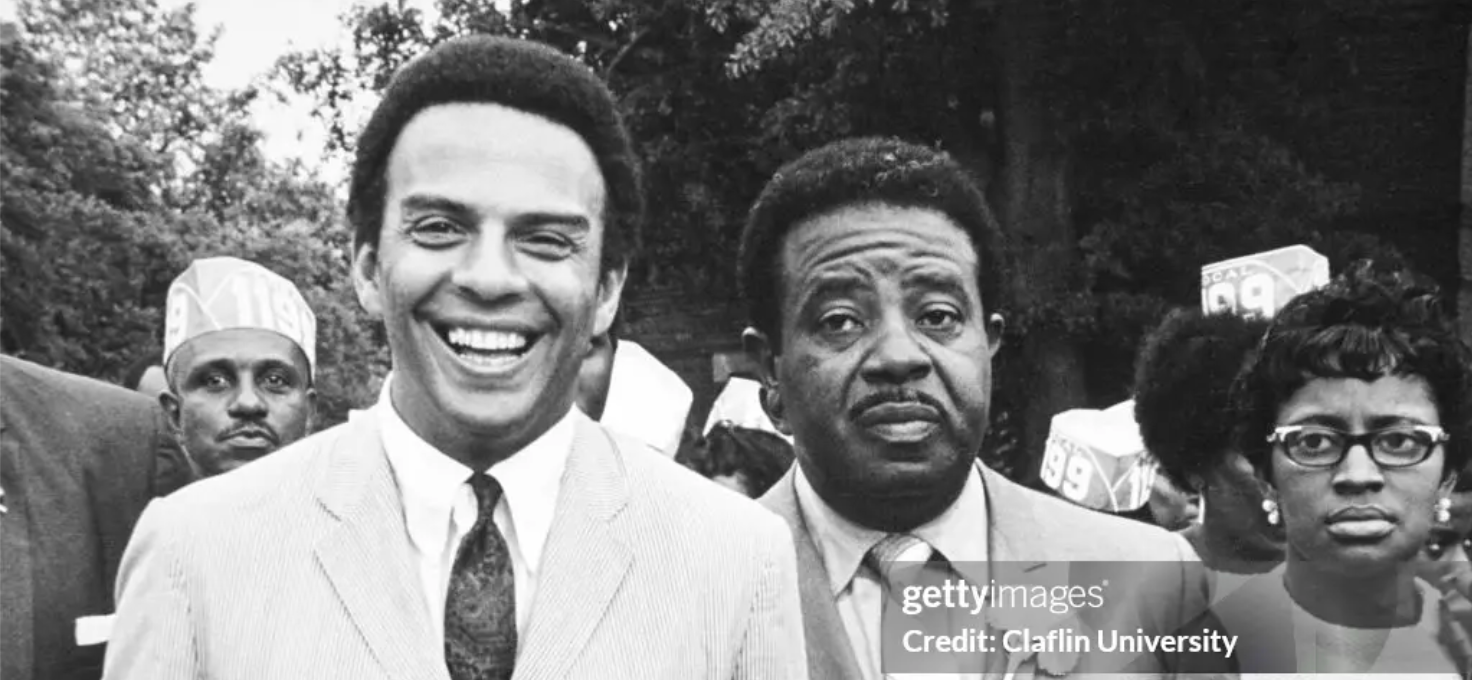

The response was swift and brutal. Twenty-eight black leaders, including Jesse Jackson and Andrew Young, gathered at King's grave to condemn Abernathy publicly. Coretta Scott King sat in what observers called "stony stillness" at Abernathy's funeral years later. A man whom King called "the best friend that I have in the world" in his final public address had been systematically written out of the story for the crime of truth-telling.

At a press conference defending his book, Abernathy said: "Martin was my closest friend, my buddy... For years, he had been placed in the position of being a saint, a Jesus, a God, but he was merely mortal, flesh and blood... If I hadn't written about what I saw, they would have accused me of whitewashing history."

What made Abernathy dangerous was not just his proximity to King, but his formation. Abernathy served as a Platoon Sergeant in World War II, deploying to Europe with a segregated unit before illness sent him home. His unit continued to the Pacific, where his black battle buddies were slaughtered after insufficient training—men who had volunteered to defend freedoms they themselves were denied. Abernathy survived to return to an America that refused him the citizenship he had risked his life to protect.

This created a particular kind of witness, a more concrete martyrdom than the binary culture warriors are willing to tolerate. Veterans like Abernathy had given freely, expecting nothing but what every citizen deserves, and received betrayal instead. They understood sacrifice not as abstraction but as lived reality—the voluntary surrender of safety in service to a democratic ideal that did not yet include them. That formation made them dangerous to those building political empires on managed narratives.

Those with earned moral authority from voluntary sacrifice get marginalized by those monopolizing authority through embellishment and narrative control.

King, for all his courage, was a civilian. So were Jesse Jackson and Andrew Young, Abernathy's chief accusers. They advocated brilliantly for rights they were denied, but they had not experienced the specific moral education of military service: learning to trust your life to flawed humans, including the most corrupt among them, in hope they might choose something better. Combat forces a dense theological reckoning—you see the worst and best of humanity compressed into moments, and your survival depends on believing in the possibility of repentance and transformation. War teaches you that survival is meaningless without hope.

American civil(ian) religion cannot afford such honesty. We have made King into something the Christian tradition reserves for Christ alone: a figure whose moral authority is validated not by mere character but by moral perfection. This serves a specific political function. If King was fully human—flawed, conflicted, capable of both greatness and failure—then his accomplishments become more remarkable, not less. And if King was just a man who did extraordinary things, then others could do them too. The greatest threat to monarchy, to the consolidation of political power, is the knowledge that everyone is capable of extraordinary things. That is the dangerous audacity behind “We the People.”

That possibility is intolerable to those who have built careers managing King's legacy. The saint can be venerated but not emulated. The savior can be worshiped but not followed, at least not too closely. And not without paying proper feilty to his self-proclaimed apostles'

Consider what testimony we reward and what we punish. David Garrow's Pulitzer Prize-winning biography documented King's infidelities, including extensive interviews with Andrew Young. White institutions celebrated this scholarship. When Abernathy, who actually lived beside King through the movement, testified to the same complexity years later, 28 black leaders gathered at King's grave to condemn him. The lesson was clear: critique of the icon is permitted only when it flows through proper, racialized channels, not from first hand witnesses with earned authority whose testimony threatened the monarchy of memory.

This pattern extends beyond Abernathy. Veterans who challenge progressive narratives face systematic silencing unless they prop up predetermined talking points. Progressive movements use veteran voices as moral props while refusing to center veteran experience when it complicates the binary narrative. The throughline is clear: those with earned moral authority from voluntary sacrifice get marginalized by those monopolizing authority through embellishment and narrative control.

Abernathy understood what democratic citizenship requires. His crime was not revealing King's failures but insisting on his humanity; the same flawed humanity we all share, with all its moral complexity and democratic possibility. He refused to participate in creating a political idol, even when that idol bore the face of his closest friend.

The King we venerate makes democracy impossible. If only saints can lead movements, then the rest of us are excused from the difficult work of citizenship. We can wait for the next messiah rather than accepting our own capacity and responsibility for political transformation.

Abernathy chose the man over the myth and was crucified for it. We should ask ourselves what it costs us to keep choosing the myth—and what democratic possibilities we sacrifice to maintain a politicized monopoly on memory.