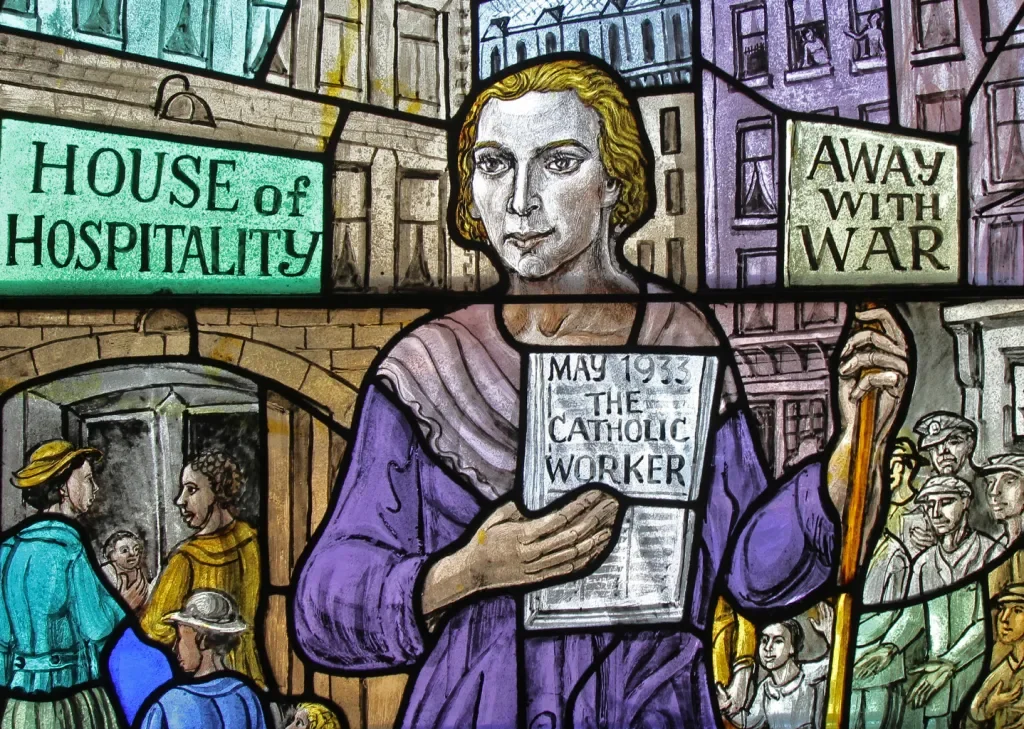

Houses of Hospitality

Peter Maurin believed that society could be rebuilt from the ground up if ordinary people took responsibility for one another. His most enduring idea was the house of hospitality: a place where the stranger is welcomed, the poor are fed, and the sick or weary can find rest.

What They Were

A house of hospitality was not a homeless shelter, nor a soup kitchen, nor a parish rectory—though it borrowed pieces of each. It was usually just a home opened to others. Some were storefronts, some were apartments, some were farms. What bound them together was a commitment to personalism: the belief that every human being carries infinite dignity, and that care should be given face-to-face, not outsourced to institutions.

In these houses, people in need were not clients or cases. They were guests. And those who offered the welcome were not staff but neighbors. Meals were shared around the same table. Clothing was passed along in a spirit of friendship, not charity.

Why It Mattered

Maurin’s houses were a critique of both state welfare and private charity. He saw how bureaucracies could dehumanize the poor, turning them into numbers and files. He also saw how charity could become a way for the wealthy to ease guilt without changing the system that produced poverty.

Hospitality, in Maurin’s sense, was about leveling the field. It dissolved the wall between giver and receiver. It reminded everyone involved that we are bound together, and that no one survives alone.

The Spirit Behind It

Voluntary poverty: Living simply so that others might simply live.

Community over efficiency: Meals cooked in bulk, clothes shared, no profit margin to protect.

Restoring dignity: Offering a bed, a bath, or a bowl of soup as if to Christ himself.

Decentralized action: Anyone could start a house. There was no headquarters, no master plan—only a shared conviction that hospitality was the first building block of a just society.

Lessons for Today

The Catholic Worker houses of the 1930s emerged in the middle of the Great Depression. But the need for hospitality hasn’t disappeared. We still live in a world where people slip through the cracks: veterans with PTSD, families evicted by rising rents, immigrants seeking safety, neighbors numbed by loneliness.

For Grunt Works, Maurin’s insight opens doors. A house of hospitality could mean a literal home, a spare room, a community storefront, or even a local gathering place where veterans and civilians can meet on equal footing. It doesn’t have to be polished. It just has to be open.

Carrying It Forward

The genius of Maurin’s idea is that it was both humble and revolutionary. Anyone could practice it—whether they owned a house or not. All it took was a willingness to share what you had, however little, and to see Christ in the person at your door.

At its core, hospitality is not about grand gestures but daily faithfulness: a meal set aside, a chair pulled up, a listening ear. For Maurin, this was the seed of a new society: not a program imposed from above, but a network of households below, slowly reshaping the world by practicing welcome.