#GruntGod ch.9 (Martin and Hagiography)

The ninth installment of a revolutionary exploration of faith and service.

What does it mean to carry the weight of other people’s devotion?

Martin of Tours’ Vita shows how even saints can be trapped between humility and veneration, celebrated to the point of distortion.

Aaron Weiss, lyricist and frontman of mewithoutYou, now teaching anthropology, joins us to explore ego, authenticity, and what happens when art, faith, and power intersect.

Chapter 9 of the #GruntGod Season Pass includes:

📝 A revised chapter exploring Martin and hagiography.

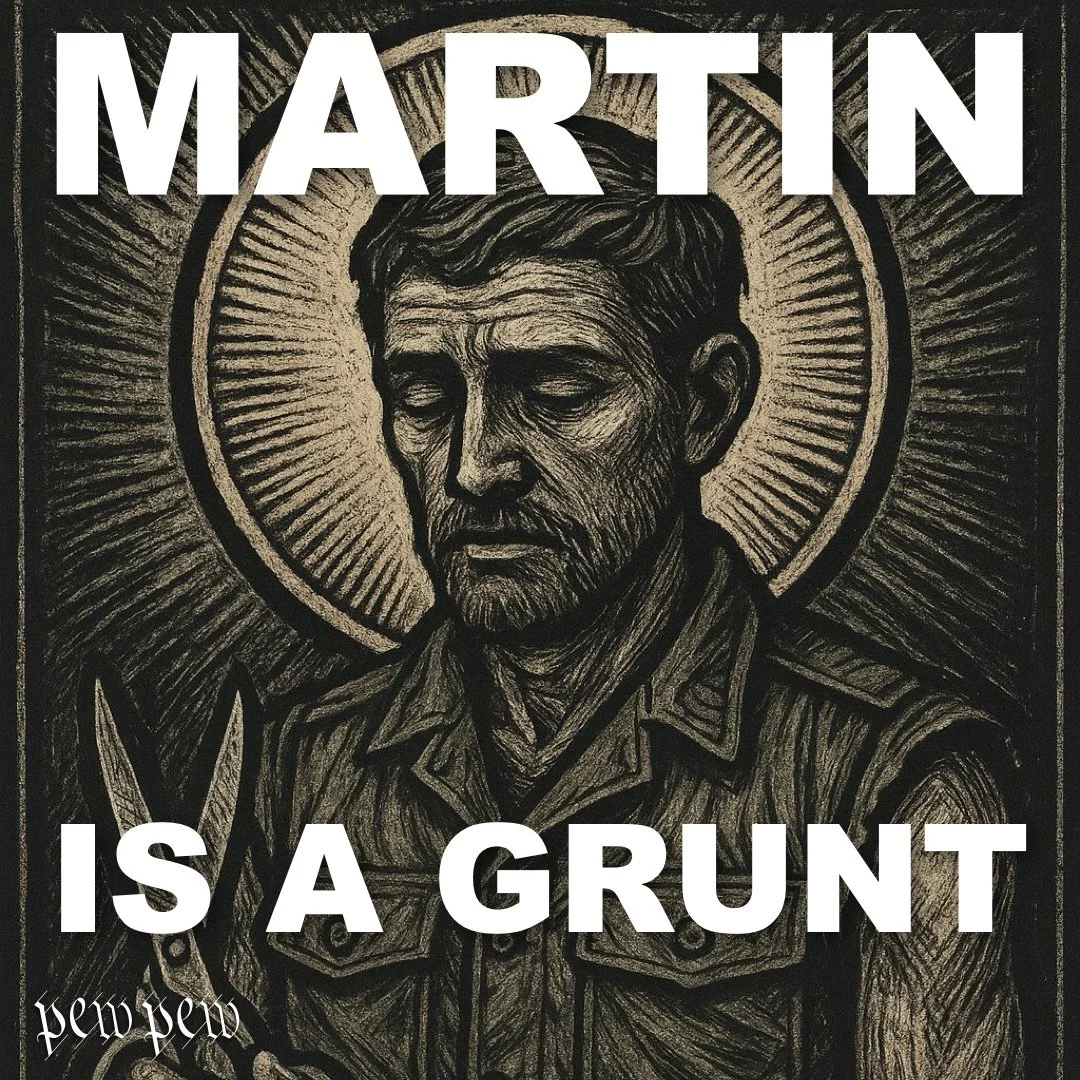

🎨 An original digital icon of Martin the Lifer—part of the GruntGod Icon Series

🎧 A high-quality, ad-free MP3 download of the podcast episode, featuring exclusive insights from Aaron Weiss.

Support Grunt Works

Your purchase helps support our mission to build a better theology for those who serve;

📚 Buy e/books via Bookshop

🎧 Buy audiobooks via Libro

💰 Donate directly via Venmo

Transcript

-

Welcome back to #GruntGod. This season we've been exploring the lives of the Saints, prophets and figures whose stories still unsettle us today. Normally I sit down with scholars or historians who can help unpack a life from the outside. But this chapter is different because with Martin of Tours, I've spent so much time in his own world that I feel like I've crossed over from student into something more like peer.

Martin's Vita, which you can access and read on your own, which is also his life story written by Sulpitius Severus shows a man constantly wrestling with power, authority, humility, and a temptation to veneration. He doesn't write a word himself, and yet his life becomes a mirror for questions that we still face in our own day.

How do we honor someone without turning them into a relic? How do we lead without making it about ego? Martin's icon for this episode shows him downcast, which was inspired by his statue at the top of the basilica of St. Martin in France, and his basilica is separate from the cathedral because he never lived in the cathedral.

He was made bishop of Tours by acclimation and. By surprise being led out of the rural villages that he preferred into the urban center under the auspices of needing to heal a an ill woman when he gets there. The bishops who were expected to make him a bishop by placing their hands upon him, didn't like the way he looked.

His hair was all messy and he smelled funny. And they didn't keep it to themselves. And so the townspeople had something rather curt to say to the bishops that didn't like Martin's un- adorned ecclesiology, he lived in caves across the river Loire, eventually compiling something like 80 disciples. And never living full time in the cathedral.

To this day, the cathedral in Tours is big and ornate, and it has, uh, all these gothic influences. But 📍 the basilica is a simple Roman style basilica, it's beautiful in its simplicity. In contrast to this decorated. You know, very, um, formal cathedral.

And in the cathedral they have some of the largest, most numerous bones to belong to a saint I've ever seen. They have a large part of his skull and a femur and some other bones that reside just below the altar in a crypt below the main floor.

Bringing us back to Martin's icon, looking downcast, not only from the top of his basilica looking down on his people, but not ambitious, not tempted, but feeling for the people of not only his urban see, but of the rural communities and the small churches that he founded. When he died, he was actually at one of these small churches in Candes up the river. When the urban elites heard that he had died, they came, took his body from its resting place. And spirited away up the river to the cathedral where his bones now reside.

And so there's even this wrestling between veneration and popularity and urban cities and concentration of people to the life that he seemed to prefer of solitude and quiet rural, living amongst Pagan families and their rituals and challenging them to come closer to God by finding and destroying everything which was not God.

And in his icon, he's cut off his sleeves of his uniform. 'cause in the anti-war movement a lot of people would deface their uniform to show that they still were a part of it and yet had somehow broken free from these false gods. And so Martin has a pair of scissors in his hands , to symbolize... he had a sword when he clothed the freezing beggar in am. But had he had scissors, I bet he would've used those to deface his uniform in the pursuit of justice. So to explore these questions of humility and performance and power and authority, I wanted to talk, not with another historian, but with a friend whose journey has been bound up with these same struggles.

Aaron Weiss, former front man of mewithoutYou, and now teaching anthropology has been in my ear lately about presence, humility, and what it means to live authentically when others want to put you on a pedestal. Aaron and I met in, I want to say 2007 when I was living in Camden and he was living around Philadelphia.

I was aware of mewithoutYou, I maybe had been listening to them. I don't recall. But we were there for a meeting organized by Shane Claiborne and Sister Margaret. Sister Margaret makes a couple of appearances in Aaron's lyrics. She's a nun who's fiery like Deborah .

But you wouldn't know, just looking at her, you'd think that she's just a charismatic, uh, hard charging woman who will not tolerate injustice. This meeting was organized to consider whether or not we would engage in what is known as a Plowshare Act or Plowshare Action, which have taken many different forms, largely associated with the Catholic Worker movement, which has been an inspiration to me and to Grunt Works.

But some of the actions have included. Spilling donated blood on draft cards in Hawaii by Jim Douglas in the sixties, The burning of the draft cards by the Camden [28] I think. Uh, and Camden, the Catholic priest in Camden when I was there, father Michael Doyle, he was one of the priests that burned these draft cards.

And the way that the stories are told in Camden is he was. Relegated exiled to Camden for that action by the church. And what happens in Camden with the help of Chris and Cassie Haw , Andrea Ferich, Melissa Pacella, like what they did for a handful of years there to restore that community as much as they could.

So that's where (Aaron and I) met and I recently gotten back in touch to talk about what we do with this moment that we're in and authority that might be given to us, or attention in our attention economy. And so today's episode is a little different.

Uh, it goes on really long, and so I'm keeping this intro short as possible, but this episode is less about 📍 presenting Martin as a saint from the past and more about entering his struggle through Aaron's story through my own. And maybe through yours too. Let's get into it. Here's my interview with Aaron Weiss of the College of Idaho, talking about veneration and hagiography and, and how things are sanctified, holi-fied, and not just texts, but lives and the texts that lives produce.

I hope you enjoy, and I hope you'll join us at Grunt Con in October 25 and, go grab your #GruntGod season pass at pewpewhq.com/merch.

-

Do you want to share a little bit about, we've known each other for time, but we've really gotten to know each other more recently.

Why don't you start with where you're at, at the College of Idaho and how you got there? 'cause I think some of my listeners would be kind of interested to hear that, that trajectory.

Sure. Yeah. Thank you. I, um, I've been working, I think it's my sixth year now, teaching anthropology at, uh, a liberal arts college in Caldwell, Idaho, which is about 30 miles, uh, northwest of Boise.

So I, and I live about eight miles from. The College of Idaho in a town called Nampa. So I, I moved out to Nampa, well, when I got married, my, my wife is from Nampa, Idaho, and so when we first met, she came out to Philadelphia, uh, for a while and lived in New Jersey while I lived in Philadelphia. And then once we got married, actually we still had that arrangement for a while, and then we went back to, um, Idaho and state a while.

We kind of bounced back and forth, and then at some point, COVID hit, um, yeah. And, um, it, it was impossible to keep Toursing. And with my, I used to, you know, my, my previous career as a musician, so, uh, I started looking for things to do to keep me busy or feel productive. And I saw there was a job opening teaching anthropology at the College of Idaho's, the part-time thing.

But I'd, um, I just thought I'd, I. Put in an application and I got hired just for part-time and then that turned into something full-time and then, um, kind of became more, I was able to kind of transition out of my, my previous career. Toursing a lot was really hard to be away from my family mm-hmm. For stretches of time.

And so I was grateful, uh, as sad as I was to leave that behind in many ways. Um, I was grateful to transition to a job where I could have, um, a little bit more stability geographically speaking, and then the ability to just come home at the end of every workday and see my kids was really important to me.

So that's kind of how I landed there. And then, um, yeah, I think, uh, I think it's my sixth year at it now. So yeah, I'm kind of still strange enough I've been here, been there a while, but still feel like I'm kind of cutting my teeth and still building new classes and dropping some of the old classes I inherited and kind of making it my own.

'cause my first few years I was walking very gingerly and feeling like, well, I don't really belong here. I'm not sure how long I'll be around, but the more it's become. Clear that, uh, uh, it's at least long term enough that I'm in my sixth year. You know, I can begin to kind of make it my own and build classes that reflect my, my genuine interests and passions as opposed to just teaching what I think I'm supposed to teach about.

Yeah.

So, yeah, I love it. It's so, it's wonderful, you know, not everything about it, but there's certainly, there's nowhere I'd rather be working or teaching, that's for sure. It's, it's a great place to be. So,

yeah, and it's, I'm, I went through the academic sphere hoping to teach and got complicated. Would you tell me a little bit about, it sounds like from what you and I have talked about, that you didn't anticipate going into education, um, you were Toursing with me without you, and would you tell us about how you went from, uh, being a musician in the Toursing band to teaching?

Is that something that it doesn't sound like you were called to teach, to use the, kinda like scare quotes, Christian language. Um, but it sounds like you're very happy in there. What did you anticipate, or what did you think you might be doing and how did that transition kind of set you up for teaching?

Well, um, I actually did study, um, secondary English education. My undergraduate years. I thought I'd teach high school English. Okay. And that was, I think I finished, um, with that right before, uh, the, the band to which we're referring started, you know, my band me without you started. Um. Making records and Toursing and kind of becoming a career.

Um, so I had this idea of teaching, uh, actually mostly just because, um, I liked English and literature and it sounded nice to have summers off, and I thought there'll always be a need for teachers. So it was just, yeah, it didn't feel like a sense of a calling. Exactly. It was more just like, I literally went one day to like a job fair and they gave a pitch about how great teaching is and summers off and whatever.

Yeah. And I thought, well, that sounds nice enough. And I, so I, I did English education, but I definitely enjoyed the English classes more so than the pedagogy classes. So I really loved the literature and the poetry that I was studying, but then got into music and I wanna say, excuse me, I don't know why I keep having to clear my throat, but

That's fine.

Um, it was maybe for the next, um, eight years or so, I'd say the first, um, seven years of the band's existence that I was just did that, it was, you know, it was, it was, uh. It was rewarding and it paid the bills. And I didn't think about having another job, but I started to spend time with a, um, someone named Sheik Moha is like a guru figure, sort of like a spiritual teacher that I know you and I have spoken a little bit about before, but for anybody listening who's never, you know, isn't familiar with that character, um, just somebody who I met that I thought had wisdom and would I trusted his insight and his guidance in my life.

And he, uh, told me to go to grad school and I actually wasn't interested in that at all, but he really wasn't insistent upon it. And eventually kind of broke me down and took me to my undergraduate institution, got my transcripts, and like, walked me through the process and so said, yeah, you're gonna study education.

And so I got my master's in teaching, learning and curriculum. And then I finished that and he said, okay, now go for your doctorate. And I was just sort of at that point, I actually, I was, I wasn't as reluctant because that at that point I had kind of started to, I don't know if I'd say fall in love with higher education, but I had start to see.

Um, to recognize the benefits of being in an environment where you're, you know, challenged to think carefully and precisely and, you know, yeah. Given a structure for reading, you know, challenging or outstanding, uh, works of, of te of prose or whatever. Um, and so I kind of started to see, yeah, okay, higher ed isn't just total baloney, you know, there's something there I think is Yeah, kind of cool.

And so I, you know, I did my doctoral work and that's where I kind of, actually, it was during my master's program, I was turned on to anthropological research methods that I found about ethnography and participant observation in different ways of studying culture that are more immersive and relational, uh, as opposed to like the stereotypical image of like the, you know, a laboratory scientist in like a white coat and like a bun and burner or something like that was a version of science I'm sure I was familiar with.

But, but as far as doing research, I never understood. What, you know, ethnographic research was, or how to research culture until I encountered those anthropological methods. And so that's where I got turned onto anthropology and studied some philosophy. Um, and then, you know, just, um, graduated, got, you know, went through that.

And then it was kind of in the, in the gaps between Toursing like we, we tore in the summers or during spring break or you know, in these little places. It, the Toursing life changed quite a bit while I was in grad school 'cause I was doing both for years. Mm-hmm. And that was very difficult. But then once I finished with grad school, kind of dusted off my hands and said, well, good riddance, I'm, I'll go back to doing music.

Few years went by and that's when COVID hit. And I happened to have, you know, the, the, the, the formal education or credentials to where I could apply for a teaching job at a college and even be considered. And I was very surprised to get the job. And then it, it was just nice that it worked out. Like it kind of start to.

Gained some experience with that while it was clear that the band was unwinding, because even before COVID COVID hit, we had actually agreed that mostly for me, due to family reasons, that I said I really would like to show up as a, as a, as a father, more so than like, you know, I really like, and, and that was much more important to me than like, whatever I enjoyed about the band.

So I realized this, you know, it's probably a good time to start to, you know, bring the ship into Harbor, you know? Yeah. Yeah. And that kind of coincided with COVID and taking this job where I could teach part-time and I could do both teaching and the band for a couple years as the one was coming to an end, the other was getting started.

So it kind of was this crisscrossing thing where, um. It all worked out really well for me. And so, uh, I still do teach about, you know, a little bit about music where I've like, brought in my guitar and sang at the school or played piano, uh, for a weird project with my class, you know? So I still do music a little bit.

Uh, we have a monthly sacred harp singing where You, you you came to actually. Oh, wonderful. Yeah. But, um, we have it at our house, so I invite everyone from the school community. I have some of my, uh, colleagues, uh, fellow professors there that come and sing every month, and a handful of students that come.

So, you know, I have a little ways of playing music still, or staying a little bit active with music, but gosh, it's been, it's been, um. It's been a, a steep learning curve and kind of, I don't wanna say all encompassing, but the first few years of teaching, it was really hard for me to kind of gain confidence and gain a sense of, um, you know, worthiness to do to be a teacher, even though that hasn't a big asterisk.

That really my approach to teaching isn't so much about teaching, but being a perpetual learner. Yeah. But that's a kind of a digression. So that's a, hopefully that's not too long of an answer. No, I think that's

perfect. But I did want to go back because I think for a lot of, a lot of folks in, we'll just say America, the idea that you would go to someone Sheikh Mohaideen and they would tell you to do something, and you perhaps not unquestioning, but you do it.

And one of the things that you and I have talked about is with, you know, a after spending six years in the military, there's a certain comfort in like letting someone else make the decisions. Um, and then as I've grown older, I, I hear echoes of it and what you've described like. Uh, there's a certain serendipity that you can discover when you let yourself go.

Your ego or your agency is not, is not front loaded. I think in the West, we're taught we're, we have very strong egos in the West, and it was being, for me, being a lower enlisted service member for a long time and not having a whole lot of control, that taught me to appreciate the things that happen outside your own control.

And I don't know if I would've learned that, if I'd like, I wanted to be for the short time I was gonna be an officer, uh, for the money mostly. But also, like, again, just like you were saying, I, I had the incredible privilege to begin teaching after my first master's degree. And I was bright eyed and bushy tailed, and they had me teach the Bible as, as literature to a, a, it was Methodist University in Fayetteville.

North Carolina. And so most of the students didn't want to be there. It was like a requirement because it used to be a Methodist school and everybody was required to do a religion class and all the professors didn't want to teach it 'cause nobody wanted to be there. And I took mostly ethics. I didn't really do Bible stuff, but I taught with five semesters of the Bible at Methodist University and really began to enjoy it.

Like my, my partner Laura Marvels at like how much I know about the Old Testament, but like it fascinates me. And when you enter a classroom, I would love to hear if this is your same experience, like the students, like a having to teach. Puts the responsibility on you to learn the material. I think it was Carl Bart, who's this big theologian guy, said I wanted to teach Luther when I started teaching 'cause I wanted to learn Luther.

Um, and my favorite thing is not teaching. I don't like getting up in front of a bunch of people. I love learning and asking questions and discovering. Paint for me a picture of like within the, the relationship that you had with Sheikh Mohaideen. Um, I also know, and you've been open about when you were younger, your family was a part of a community, um, that was led by, uh, uh, Indian, I think guru. Am I, is that correct or am I way off base? Maha Sri Lankan.

Sri Sri Lanka. Yeah. Right off the coast. So the southern tip of India. Okay. And. Forgive me, but I, I think a lot of people will see that as, that feels very foreign to a mainstream imagination, I think, and I am frankly encouraged by the idea that a community that assumes a certain commitment, assumes a certain membership.

Um, that it doesn't, I, I don't know. Or I think you said that you were very young, but when you were receiving guidance from Sheikh Muha that was still within kind of that community, would you tell me a little bit about your understanding of what, and this we can use to begin speaking about. Uh, today, this episode's topic of hagiography, which comes from the Greek hagga, which is holy or sacred.

And then graph or graphic is typically like autobiography, biography's writing. Um, but writing is, is a certain system of meaning that resides within a greater system of meaning. So I, I want to think about like art and music as a kind of, uh, hagi force in people's lives. I mentioned, uh, boa Muha because I, uh, one of my favorites, uh, works of yours is the, the king of the coconut estate, king of beetle on the coconut estate, which you adapted from one of ba modi's, not treat it, what would you call it?

The, the divine luminous wisdom. He didn't write it. He, his students would sit and listen and record it. And we're here to talk about, well, not necessarily Martin, but Martin of Tourss, my patron saying he didn't write anything himself. He's known and I know him because somebody else saw in him something good for, we'll just leave it at good and thought, you know what, when he dies, I want that to persevere.

I'm gonna write his life story. And the gospels are four perspectives on Jesus's story that were written a couple of decades after his death. But humanity seems to have this proclivity to venerating, to putting others of us on a pedestal. And here I'm, I'm also like very self aware, like military veterans in certain communities are put on a pedestal and that has a certain dehumanizing, or it can, it can have a dehumanizing effect on that individual and.

I, I'm toying or, or like, dancing along the edge of like, community of, of cult. Cult is a unit of culture. But when we think of cults, we think of cults that have done things. Harmfully. I think there are cults that do things unharmful and healthfully, but the more difficult aspects, the, the, the failures are so much easier, it seems to remember than its successes.

Would you tell me a little bit about your understanding and your experience within, I don't know if Colt can be deprived of its negative connotation, so feel free to tell me that's not an appropriate word, but I, I just don't know how else to begin talking about culture in kind of the microcosm or the, the, you know, not like 300 million with America.

I mean, churches used to just exist in houses. And then Paul had this way of systematizing it, which becomes institutionalized religion. And a lot of people, including myself, are kind of over institutionalized post-industrial religions. And uh, that's one of the things that interests me in your approach to teaching, learning, um, art, um, the Sacred Heart when I went there is just, I mean, I'm sitting in the chapter house, which is a bookstore I opened that's inspired by Tolkien, whose creator God in the Lord of the Rings.

It's all about singing and harmony and evil, for lack of a better word, comes out of dissonance. It's not like bad. It's something just isn't quite fitting. And instead of aligning with the other voices, it takes a certain interest in that seclusion, that identity, that ego. Anyway, I'll stop rambling, but I, I'd love to hear your feedback and your reflections on what being approximate part of that community, whether it's a cult or not had on you, and what good it did and how that, it seemed to help you kind of find this place in teaching in academia that isn't necessarily, you know, it's not like an Ivy League school.

I was a high achiever. I had to go to Duke and all the rest. But once I was there I realized like what I'd really love to do is just sit in, sit in a classroom all day. Um, and so what I've learned, maybe as a roundabout, less than the best way it sounds as though, it sounds as though you had a much better experience of, of power structures, maybe.

Well, I, I would say, uh. I'll start with, um, maybe the most, uh, direct way to respond, uh, that I can think of to, um, one of the points that you made about, um, Bawa not having written down the story. So yes, the, the, the song to which you refer the King Beatle being based on one ABAs stories, um, and the, it's an important detail that you note that he didn't write that down, at least in insofar as I'm trying to under, uh, I'm kind of understanding your interest in hagiography or sacred writings and someone writing down what Jesus had to say or writing down what Martin of Tourss had to say.

Um, there's a story about ba Mohaideen that was relayed to me by. So maybe I should actually back up and say when Bio Mahaine was alive in the world. Um, he died in 1986. Now I was born in 79 and my family was kicked out of the fellowship when, um, when 1980, so when I was a baby. And then, um, my parents weren't allowed to go back until 1996, about a decade after Bawa had died.

So basically my entire upbringing between my birth, you know, between the time I'm 1-year-old and the time I'm 17, um, I kind of was raised with BAA's teachings, but I had never went to the fellowship. I had absolutely no memories of ever being there other than my parents. My, my, my mom used to literally pay me to go because, uh, my parents were kicked out, but I, my brother and I were not.

So we were allowed to go, and I think she so wanted us to maintain a connection to that place. By the way, they were kicked out for pretty understandable reasons. My dad suffered immensely from various diagnoses of mental illness and. Threatened violence in ways that he, it was understandable that they said, Hey, you can't come here if you're gonna talk like that.

And you, you know? Mm-hmm. So I did not di villainize them for kicking out my family. It made good sense. The point is, I wasn't raised there. Yeah. And so it really wasn't until, um, even, um, 12 years later. So here I'm 28, 29 years old that I'm even met Sheik Mohay. I just started to go to the fellowship because I discovered the poetry of Rumi, which had been translated in, um, by a guy named Coleman Barks, who was a disciple of BAAs.

So I found Rumi's poetry having been raised in the Sufi context, and then I found various church communities and identified as Christian as opposed to being Sufi. You know, I was like, oh, I'm not Sufi, I'm Christian. And then started to read Rumi's poetry after. Um, some time and kind of melted my heart and I just fell in love with his, you know, with, with his ideas and his imagery and sort of realized, well this is from actually my own, the tradition of my childhood and I really don't feel the need to keep this at arm's length and sort of be, define myself, uh, in opposition to ufm.

And I began to sort of integrate Sufism into my life and to embrace what I consider to be the best parts of Sufism and see that much of it did align with what I found was the best parts of Christianity. And then it gave me a sense of this kind of, you know, perennial philosophy approach to religion, I guess, for lack of a better term.

Just sort of like, well, if there is a truth, which I believe there is, it would make sense. That it's much bigger than any particular human tradition or particular language or particular book. It's something that would probably show up or humans all around the planet would have an intuition about it or some insight into it.

Or you'd notice commonalities in our

Yeah, yeah.

Um, moral systems or our values or whatever. So basically I started to kind of try to synthesize the teachings of, um, the, of Christ and the teachings of Bawa and the teaching of poetry of Rumi and basically whatever else I'd get my hand on that set that seemed like it was worthy of the title wisdom, you know, like the, the category of wisdom teaching.

And so I started spend time with Sheikh Mahaine. I'd go to the fellowship and kind of poke around and I would sort of say the prayers with the people there in the way that they prayed. And I'd listen to the, you know, play videos of BAA's discourses or his, you know, like sermons. They call 'em discourses and, excuse me.

And I was encountered Sheikh Maha. And he would go there and sit, and he was clearly very different. He, his, his approach to BAA's teachings and his life was extraordinarily different than anyone else there that I encountered in so far as He wasn't a part of the executive committee. He didn't get up and leave meetings, he didn't have a position of authority, wasn't actually viewed with a great deal of respect by most people.

From what I could tell. Some people just thought he was crazy. Um, but to me, when I listened to him, he clearly spoke with a sense of authority and an inner authority, like a spiritual authority. Not because he's in a position of institutional power, but because his words were intrinsically powerful. And his presence to me was intrinsically powerful.

So the authority was self-evident to me. Uh, I guess you'd call it charismatic authority in vapor's terms. You know, it's basically, wow, this guy has exemplary characteristics and, and, and insights that I find valuable, um, despite his lack of. Formal religious position. So I just was drawn to him and I spent more and more time with him, and it began to change me and it began to break me down in some ways.

And really it was difficult. It was painful because he was very honest and confrontational and at times, perhaps harsh, but in ways that, looking back, even at the time, I knew I had a very clear sense. It was for my own, for my betterment. It was kind of cutting away things that were clearly false and shallow and hypocritical and, and, and, and harmful.

Mm-hmm. Um, but it still hurt. So being with him and being in his presence was, is the, to this day, the single most powerful, transformative kind of condensed period of my life, just a few years where I went to sit with him for hours and hours of sometimes 10 to 12 hours in a given day and just listening or just being with him, with no agenda and no plan, but just, okay, here I am.

I'm here to. You know, for, for whatever it is that you've got, you know, let me have it. Mm-hmm. Um, and there's something about being in the presence of someone who was in that state. It was very different to me than even, you know, reading the red letters in the Bible where whatever you think about Christ or Jesus and his character, or his divinity, his wisdom, whatever I'm sure a anybody listening could recognize there is a difference between being in the presence of someone, being in the presence of a living teacher, someone with greatness or with wisdom.

And on the one hand, and, and reading an account of their life on the other that's been mm-hmm. Translated, or it's literally just sitting on a, on a page that isn't literally alive and doesn't look you in the eye and you can't feel that, hear, hear the tone of voice or feel the, the presence in that intangible way that what happens when human beings come together.

So, um. This is a long roundabout way of me getting the story that Sheik Mohaideen told me about Baha Mohaideen, which was at one time BA was in his room giving a discourse. And he's talking and talking and they're recording him as they always, as they tended to. And then the discourse was over. And the story he told me was this one of BA's disciples took the tape outta the cassette recorder and began to leave the room.

And Bawa said, Tobi, which means Brother Tobi, where are you going in Tamil? Bawa didn't speak English. He said, brother, where are you going? And the person said, oh, I'm going to transcribe this discourse. And Bawa said, that will do. Nobody any good. Won't do anybody any good for you to go type up what I just said.

Not gonna do anybody any good. Um, maybe there are more stories where Bawa approved of the recording of his. Sermons or his discourses. Yeah. Or were help to compile the books. I don't know all the stories, but the way that Sheikh Mahaine described that to me was he, he, he described BAA's books as the droppings of a beautiful bird.

He said it's basically they were bird poop. B was this beautiful bird that came into the world and was captivating and we all were mess. We all fell in love with him. And he said these things in real time and his presence was transformative and his love was so palpable and so nourishing and so healing.

And we could either fall into that and merge our life with him and become more like him and more of him. Um, or we could record the things he says, type them in a book, bind it together with a pretty co cover, sell the book and study the book, and debate the book and talk about the book and quote the book.

And in doing so, shake Maha's, take on it was all that stuff we do about. Recording and binding and prettying it up and selling it and debating it is all a way of keeping the, the living presence at bay. And it's a way of intellectualizing the whole thing or institutionalizing the whole thing. And to this day, there is a bide fellowship.

Is it religious? Like five? I'm sure it's a 5 0 1 C3, like tax exempt organization that is committed to the proliferation of BAA's teachings when for Sheikh Sheikh Mahaine that it was not the point to, to proliferate BAA's teachings in text. The point was to embody BAA's teachings or to be, to merge our life with, with the wisdom and with the purity that Bawa embodied.

So it's not to say that I did that by any means. Not even close, but. Say that in what I saw in Sheikh Mahaine was somebody who had no interest in selling BAA's books, but who was interested in embodying and channeling BAA's presence and becoming the sheikh, or becoming the guru, becoming, uh, or attaining the, the Christ consciousness or whatever the language we have for it.

It was about that living, uh, presence as opposed to, um, the, the, the written text, which is in a quite literal sense, not alive in the way that a physical, a human being is. Does that make sense?

No. Yeah, absolutely. It strikes me as like a relic. Um, for a long time in Christian history, there's this whole, like, saints would die.

And their bones, they'd get buried and they'd preserve their bones or they'd dig up their bones. And this is true of a lot of indigenous cultures as, as well, like in, I spent a lot of time in Hawaii and the bones are in, uh, before contact. The bones were where your spiritual power resided and you'd, when a powerful person died, they'd bury 'em in secret so that nobody could steal their mana.

Um, and Christians did this as well. They kept like little chips of bone and they put 'em in these cute little reliquaries. And I hear all that and I agree, and I also wanna say, but because we live in this world where like not everybody has a Bawa or a Christ. And what I hear described at what I hear described is like a good, a healthy family.

Um, and that's where I think like. A healthy family. I don't love the whole nuclear family crap, but if there's anything that inspired me or, or, or reminds me to be good, it's the fact that I'm a dad, that I have children that are my responsibility to make good so that they can then kind of propagate, multiply good around them.

And that's, it's the greatest challenge. And so the instinct of, of sanct sanctifying people, um, I can, there's a, there's a, a kernel of good, but I'm also like very much with you, like how far do we go down that line before we recognize that it's not futile, but like where is the point of too much? Where is the moral compromise?

Too much? And Martin and Christ didn't write anything and. It. I didn't even think about that with Christ until I, I wished Martin had written something. 'cause he was in all these, you know, political things of his day. He knew the emperors. He spent entire term of service in the military. Like, I wanna know this guy.

I wanna know as much as I can from as direct a source as possible. And the person who wrote his biography was an aristocrat who was, who was converted by Martin. And there's some debate over, even in the academic sphere, like the whole monastic impulse that was, that grew around Martin and after Martin, 'cause Martin was the first bishop of a major urban center to, to maintain a monastic life throughout his entire Episcopal sea.

So he lived in a set of caves across the river lair from the cathedral and Tours. And by the time he died, he had like 80 disciples living with them in caves and within. Within two or 300 years, those caves became Martier Abbey, which became like the political center of the Holy Roman Empire. Uh, not the center, a very powerful part of the Holy Roman Empire, which to me, Martin would be like rolling in his grave.

But at the same time, like I see where that impulse comes from. And then to a certain extent, like I, I really appreciated reading, uh, the Divine luminous wisdom, and it's clear they didn't put a whole lot of marketing time and effort into it, which is great. Um, but I'm, I'm grateful for that. I'm grateful for the, the king beetle that you adapted from that teaching.

And I also see, I see. And correct me or, or I, I hope you'll let me know if at least your intent was different. But I see the King Beetle, the. The storytelling, the, the stories behind the stories pair of bulls, like what Jesus is doing. Um, I, my sense is that what you did with that story found a pretty damn full flourishing in nine 10 stories where it's this whole, it's a series of parables, which itself makes a whole parable that gets into some themes that are like, I wish more people were thinking and talking about, but you've got to get you, there's, there's a certain threshold that you have to let people cross on their own.

You're not explicit in that album, and many poets and musicians aren't always explicit. Um, and that. That feels similar to that instinct of like, let's preserve what Bawa is saying, but how do we keep from people looking at us or me as though I'm the answer? Even Christ is like, and Mark, he has this Messianic secret.

He is always telling people, don't tell anybody what I told you. Don't tell anybody I'm the Messiah. Which when I read it feels like, yeah, we want figureheads, whether that's Caiaphas or Pontius pilot. Um, and so there's this, this balancing act. Um, would you share a little bit about your, the, the, the balance, the exchange of creating a piece of art, your music, whether that's the sound or the lyrics and the difficulty that I, I would've had a very difficult time Toursing.

I would've loved, I think. If, if it, I, I imagine if I had been a, a musician or maybe I will in the future, I don't know. But I imagine it's almost like a classroom. You have people's attention and you can help cultivate the good in the, you know, hour and a half, two hours you have with them. But the danger is that you, people might look to you and the embodiment of you and miss the forest for the trees.

And I hear that in some of our discussions. I hear that in other people who are, have some influence. What has that balance looked like for you between being a light and not hiding your light, but also helping other people see the light in themselves and the light outside of yourself? Does that make sense?

I think

so. Um, I think the, the easiest answer I could, could give is that, um. It's, it was complicated for me. It was complicated to try to, it, it felt like a, some kind of a, um, I don't know if there's a square peg in a round hole metaphor or if there's, um, something, a, a tension that went throughout my entire time in the band where I had this sense that, okay, I, I have a platform.

I, I would like to use it to say something, uh, beautiful or, or, uh, spiritually important, rich or helpful to people. And, um, and yet, um, here we are selling tickets to our shows, selling our CDs, so it's part caught up in this whole you of capitalist system of and desire for, you know, comfort or success or profit and, and like whatever quasi celebrity of being photographed and like signed this autograph and all these, you know, aspects of it that seemed very contrary to what I saw in.

The it, whatever I could tell of the, as like the life of Christ in terms of like, well, this guy didn't seem to be trying to become a celebrity or make a bunch of money off of this or something. You know? It was just like, yeah, wow. He had a very different message, and in fact ended up being so far from becoming a celebrity in his lifetime became, you know, it was, it was executed and, you know, penniless or whatever, you know, whatever version we have of his life is like, he wasn't a rock star, you know?

Yeah. And so here I am, like, and neither was I, but I was kind of in a, in this band where I. And some element of publicity. I was sort of a public facing to on never small scale. And it always felt like there's a tension there because it kind of, to return to my metaphor of like, we, we, we, we, we publish books to keep, keep the spiritual intensity at bay and protect ourselves from the, the spiritual flyer.

Here's a way we can kinda keep a distance from it. I think we can also get up week after week and talk about God, um, from the pulpit or from stage as a way of keeping God at bay or keeping, you know, um, the, or just in the most obvious sense. Like I, I was very well aware of the tension of like, insofar as I would claim to be representing or preaching about someone who.

Taught to give all possessions to the poor, and here I am, you know, not, instead of doing that, I'm gonna, you know, buy expensive musical equipment and travel around and talk about this guy who did that as if I had done that. And, and there's just all these complicated kind of mental gymnastics I think I kind of had to endure because of, of my, of this conflict where, you know, to, to, honestly, I, I bet if you asked any other guys who were in the band with me, at least, I'd say if you asked most of them, they would give you a lot more straightforward and, and, and, and I think an answer with probably a lot more integrity than what I have or my experience, which is like, Hey, I liked playing my instrument.

You know, I liked playing guitar. I liked being a drummer. That's why I played drums, because I liked drumming. You know, I liked playing guitar, so I joined a band and played guitar, and there was always a sense I had that that wasn't enough. And I think a lot of tension within the band is, I really tried to make us into this kind of city on a hill or this, you know, we're torches together.

We're this beloved community. There's something really me meaningful going on here spiritually. And it's not that I regret that impulse. Um, because I still value those, I still aspire to that unity and that spiritual, uh, quality of life. But the, the kind of potential hypocrisy of, of enjoying the limelight and enjoying on some level the success or enjoying the sign, the autographs or this quasi celebrity, um, in the name of the wisdom, in the name of Mystical Truth, or it just was convoluted in a way that I think just liking to be a guitar player is not convoluted, or just being a recluse who commits your life to wisdom and doesn't try to impress anybody or sell records is also simple and clear and, and, and, and coherent to me.

I, I, I, my memory is I lived a kind of a disjointed life and trying to combine these things that may be IR irreconcilable, um. And that's not to say nothing good came of it, I, or that I regretted as a whole. I, I had wonderful times. I had a great love for the guys with whom I was able to experience that.

And I believe there are lots of wonderful lessons and interesting. Interestingly, Sheik Maha had a, had a, a complex take on this too, insofar as he said, you know, you know you have to give that up and it's perfect that you're doing it. Yeah. Um, uh, and you have to give it up when the time is right. You know, you have to give, which doesn't mean you have to leave it.

To me, giving it up doesn't mean you walk away. It doesn't mean you burn it all to the ground. It's a matter of letting go of it. Yeah.

Yeah.

And not clinging to it in this way that I need this or I put my trust in this or this like ego thing. Like you mentioned the ego mm-hmm. Is a big, that content is a big kind of framework for me, for like, making sense of my experiences is like there's a way of, um, navigating through life where the ego is really in the driver's seat, this kind of self.

Centered concern of like, I want what I want, I enjoy my, my pleasures, I have my aspirations and I'm gonna, well, hypothetically, one could live one's entire life motivated by those self-centered concerns. Or of course, one can live for others or one can submit one's will to an authority spiritually or in the military or whatever.

There's all different ways and, and like modes of navigating life regarding the will and and agency as you mentioned. Mm-hmm. And I'm glad to hear that you had some experiences to kind of, you know, experiment with that or to, to taste, you know, life as a, um, as, um, what, I don't remember what your rank was, if it was like you're a private or were you a.

I had, I was really lucky.

Grunt. Yeah, grunt is, I mean, the military grunt within the military is a very particular term, and I use it liberally. You know, knowing that other people in the military be like, you're not a grunt, you weren't infantry, I was artillery. Um, I, my experience is kind of being, uh, I just don't fit in well with the structures that I found myself within.

Um, and, but the military was good because it gave you everything you needed. And if you wanted to just, if you just wanted to kind of get, th there's a lot of guys, you, you sign up and you're like, this sucks. It's basic. You're lowering list and everybody's telling you what to do, but there's a certain, at a certain point, you just kind of, we call it embrace the suck, but like.

You find ways to be happy with what little you have. Um, I was telling my, I was telling my, one of my kids this the other day. I had this magic trick. I still think it was magic. I dunno how it worked, but, uh, before nine 11, I was in a conventional unit and we do training every couple of months. And you would spend weeks in the field and you don't know when you're going out.

You don't know when you're coming home. And that's part of the thing. It's, you know, bootcamp is put you under stress. You need to start learning how to think under stress. And I'm so grateful for that experience. Um, and so we, we go out to the field and, you know, when you go out, you, you may be there for three weeks, you may be out there for three days.

So I had this magic trick. I would take a uniform and a pair of underwear. They're always brown underwear. 'cause if you shit yourself, at least you could just say you're sweating. Yes, I, I, I would desperately love to have brown underwear again. Um, but I would keep it in a, a Ziploc bag in my, in my ruck. And no matter how bad it got, I mean, there was one training problem, a field problem where it rained on us a week straight in the swamps of North Carolina.

But I, there were two things actually. The one thing, as long as I could brush my teeth at night and I knew I had a clean uniform in my ruck, I could withstand almost anything. I, I would almost, I don't think I ever actually used that uniform, but it's just that little kernel of knowledge, knowing that if it, if I really, if I, if it really breaks me, I can fall back on.

This clean uniform. And with the teeth, it was like, everything's dirty, but like all you need is a toothbrush and you've, your mouth is clean. You can tell yourself the rest of you is clean. Um, and so I think there's something of that, like I really appreciated, I, I did finally become an E five, A sergeant, but I was, uh, I didn't go through the normal channels.

I was promoted without a board. I was basically promoted without all the things you gotta do. And so I was given responsibility without having to have gone through the, the chore of all the training for it. And it was also right after we came home from Iraq in oh five, that the responsibility became very real, very quickly of, uh, I was made in E five and then we lost almost everybody above me, either to changes of duty stations or.

Drugs. And what I later realized was a suicide attempt. Um, and so responsibility kinda got foisted on me, whereas the typical kind of like path or trajectory is like if, and I had friends who like, wanted rank, wanted that responsibility, wanted that esteem, um, and did the work and earned it. And like, I, I never served under him, so I don't know, but like, I want it, it makes me wonder, going back to your comment about, uh, some of the other guys in your band, for them it seemed more straightforward forward and the implication was for you it's, it's more complicated.

And I've often thought about whether. You know, I, I think about a lot. I've got a fairly active mind and I've got, you know, the ability and the time to contemplate stuff, which is kind of like the backbone of, of wisdom. Um, and I, I don't know that I envy, well, how should I say this? I think there's something, I, I wanna believe there's something uniform, like you mentioned perennial philosophy.

I wanna believe there's something alike in all of us humans, and that's why I'm fascinated by anthropology. And we'll take a break in a moment, we'll talk hopefully a little bit more concretely within the academic or whatever fold. But I wonder if it's, if you share that sense of like, do you feel like there's, you're more sensitive to those complications?

Do you think that's acquired through your experience? Do you think that's something that you got from your parents? Do you think that's a thing at all? And I asked because my sense or my experience, I remember when I was in the military, I, I would get in trouble because, because I would, they would call me a smart ass, um, or barrack's lawyer or whatever.

But I'm, I, I don't know. I'm always thinking about what I'm doing or like the effect it might have. And I want to be conscious of my actions. Uh, when I was in, when I was in combat, I remember thinking, being self-aware that I would like to be, uh, I don't know if you watched it, but there's this movie about Vietnam.

That was produced by Oliver Stone, who's a Vietnam vet, uh, platoon. And there's three basic characters. The, the good guy, the bad guy, and the guy kind of going in between. The good guy is Willem Defoe, the bad guy. I can't remember his name, but he has the scar and he is like, yeah. And then there's Charlie Sheen, and his name was Chris T.

And I thought like, that's the kind of guy I want to be like, being self-aware. Like I want to be good. I want to figure out what it means to be a good soldier, a good man, a good dad, and actively pursuing that. And I wonder, uh, I, this is me just literally wondering out loud, do, do I, or do we, do you think that, that that instinct is different or other, or do you think it's the natural kind of like, I don't know, maybe I had the sense.

And it, it, I, it feels like it might be insensitive. I don't know. But I got the sense, and it entered my brain talking to a, an E seven I, it dawned on me, I think my brain was an E seven. What, what is that? E seven, a higher ranking, non-commissioned officer, somebody who was above me. I remember thinking, and, you know, I'm, uh, he was yelling at me for something and I'm, you know, just doing what I'm supposed to do.

But in my mind, I'm thinking, I think my brain works a little bit faster. I, I, I don't know what to do with that. And I don't know if it's true. I don't know if it is, if it's something that is human or something like diagnosable. Like we, we mentioned very briefly mental illness. I wonder if, how would you contextualize what you've said seems different or less straightforward?

Is there a name for that or do you think, like, is there no name for that?

Well, if I'm understanding your question rightly, and then you're, you're asking about the distinction I'm drawing between my experiences with the band and the other guys whose were more, whose experiences were more aligned or more internally consistent.

Yeah. And like the, the com, the complexity that I felt came from this, um, this level on which I, I enjoyed playing music too. I liked, you know, selling records and I liked, you know, being on stage. There was an energy to it, there was a fun, there was a comradery on a level which I can enjoy and appreciate music.

Um, just a very basic level, just like as an animal going through a ritual with other animals and we are doing it together and it's a shared focus and there's an energy to it. Um, what was, what was complicated or, or maybe convoluted for me was, um, doing all that, you know, in the name of. This other thing, um, introducing that the wisdom teachings or the, or the, the religious dimension, which is not, is not at all to say that nobody else in the band was religious, um, or spiritual.

But it just, to me, it was so overt that I was really trying to make it something that's so, um, explicitly, uh, spiritually charged, um, when it, it, that might not have been, uh, appropriate. So there was something to me. Uh, and so I get to address the question of human universals. I had to plead ignorance there.

I mean, the longer I spend in anthropology, you know, the less I, I think I know about humanity universally. And the more I kind of come to appreciate the diversity of our species and, and no longer presume that other people are, you know, they're really just like me. Mm-hmm. Uh, they must have really at their core.

The same fundamental longings for, uh, spiritual truth or some kind of connection to God or something, the things that are most fundamental to my life. Um, I don't see that universally. I, I do see everybody, I mean, always anywhere, any culture I've ever studied or it seems there is some kind of super beliefs in the supernatural or a spiritual bent, or a, a moral framework or some kind of idea of wisdom that's beneath the surface.

It's not self-evident that we gain through hardship or experience and time and silence or whatever. There are certain things like, it seems like that as for that perennial philosophy reference, that there's kind of a thread going all around the world that kind of, I would say, binds us together with having certain inclinations toward the search for deeper, deeper truths.

Um, but I certainly wouldn't presume that, say, uh, an avowed atheist, uh, who has no stated. Intention to connect to any deity and in fact, for whom, um, living a good life might actually be trying to argue against the existence of God because they think that would be liberatory in some way. Like, yeah. Um, the, the details of our, um, intuitions and our leanings in terms of trying to find liberation or, or beauty or goodness and truth, they differ so much that I don't put a lot of stock into, like, this is the thing that's consistent.

It's a belief in a God that binds us all together. 'cause you know, clearly on some level it doesn't, but I do think. Even folks who would disagree up and down about um, the existence of God or the divine characteristics that I to which I claim to aspire. Um, I bet when it comes down to it we would align that, uh, on having values on there.

Being some kind of on moral hierarchy of some things are just better than others, and even those who would claim moral relativism, I don't think really put their money where their mouth is. It seems that when push comes to shove, they often are willing to acknowledge that some things are simply wrong and some things are right or we should be.

So I don't know if I'm trying to answer too much by kind of. Circling back to that question of human universals. But I can say just in the context of the band, I just to clarify, I do not presume that the other guys were, you know, I don't mean to portray them as lacking in complexity. Their lives every bit as, you know, complex and intelligent as I am, if not more.

Um, but it's just that I think they, they didn't have that kind of, I, I, I, I, I'm certainly open to the possibility that it's, it's been pathological in my life. The, an obsession with religion. Which to answer your other aspect to your question, pretty directly. Like did it come from your parents? Yes. Yeah. In my case, I inherited pretty directly and I'm sort of spinning image of my dad in so many ways.

I feel like he seemed to me and he was, again, diagnosed mentally ill, but incredibly passionate, um, man of faith who had a kind of a real intense focus on the, the spiritual path, but also drew equally from Christianity. The Judaism of his youth, um, this Islamic teachings of Bawa and the kind of common ground there.

So he wasn't into like being up. Uh, being Christian or being a Muslim or being a Jew, he was into God.

Yeah.

Uh, as best I could tell. And he was so intense on that, that he really couldn't find his way through the world with any kind of normalcy that allowed him to like, hold a job or stay a, you know, be a hit at the party or whatever.

He was kind of an outcast and, um, I acquired my respect for, for that from him. And I think just also, I don't know if it was through heredity or uh, environment, but um, just seemed so much like he, I feel so much like he seemed that, I think I got a lot of it from him and my mom. But I think more so my dad had this kind of intensity that was a little bit off the rails.

Hmm.

And, and May and rendered him profoundly maladjusted in the world, um, in a way that I can very much relate to. Yeah. But also I wouldn't trade it for anything. And I'm kinda looking back, I'm glad that going through the, the punk scene or going through the being an indie rock band or whatever we were, and feeling maladjusted, I'm glad I felt maladjusted.

Uh, now working at the College of Idaho, I love my job and I feel maladjusted and I'm glad I feel maladjusted. I don't want to fit in here or there. This is the Enneagram four. And me talking, I guess my friend Paul would say, well, you're an Enneagram four. Of course you feel maladjusted, but whatever you call it, I just do feel like there's something here in me that can't align.

With how things are being done here. There's something profoundly off and I've been able to put my finger on it more or less clearly over time. And we don't have time for all those ways now. But, um, suffice it to say it was with me in the band, it stays with me to this day. And that's probably been difficult for other people.

And, and I apologize to the guys in the band and so far as I was a real, you know, pain in the neck about a lot of things. But, um, I was trying to follow my conscience and I hope to continue to, even if that creates difficulties for myself or others. I was just talking to my wife today about Ki Guard, uh, one of my favorite philosophers who, who said, gosh, everybody these days seems to be trying to make everybody comfortable.

Yeah. And he said, ah, I feel kind of called to the exact opposite. I'm trying to discomfort people. I'm trying to kind of trouble things in a way that I really respect. And he certainly seemed to walk that better than I do, but I have a similar impulse that like, I have to push back against something here.

Yeah. I can't go with the flow.

Yeah. I think when I was, what I had in mind was like. Am I overthinking? Or if it's true that I'm overthinking X, Y, z, is it also true that other people are under thinking it and trying to find an answer to that? And I think you gave a much more eloquent response. Like there's, yeah, an intensity is a word that's been used to describe me, both good and bad.

I remember, um, my sister, when we were, when I was getting married, uh, my, my sister and I were having some kind of spat at the time, and that was the word she used was intense. And then my, one of my good friends, um, my best, the, the person I, I would've asked to be my best man. It's just not his, it's not his comportment, you know, you gotta like do the mc and you gotta like, make jokes.

Another really good friend, he did that like, and I told him like my. There's a reason I'm asking you. I you're a great friend and would you be my best man? Um, and I remember we were sitting around taking a break, setting up the, the reception and my friend used the exact same word with my sister standing right there in a positive way.

Um, and it made me realize, like, yeah. And one of the things that I learned to finally say about myself, uh, I learned because my therapist at the vet center, this is in the last year, finally got me to come to terms with the idea that I might be smart because the, something has taught me to believe that if I'm smart or if I say I'm smart, then that means you're not.

And a lot of people hear it that way. I think a lot of people would hear me say. I feel like my brain moves faster. They may hear that as, oh, are you saying my brain moves slow? And that that thing, that force, that expectation or, or worldview is so dominant, you know, the expectation or the desire for comfort over growth.

Like I even like, it's written into the world. Like if you want to build muscle, you've gotta kind of rip it to shreds and it regrows. And the people that I've been the most, the, the most painful relationships for me have been the people who had the grace to say that they wanted a comfortable life. And I represented a threat to that.

Um, and so, yeah, I think what I hear in your response is that. Some of it. Yeah. Some of it may just be unavoidably in my genes. Like I, I have some suspicion about where my proclivities come from each parent, and I can see it in my kids too. I'm like, oh, you're gonna, you've got that, you've got that thing, whatever we want to call it.

Um, 'cause I all, it also reminds me like by being myself in front of people who are not like me, it helps other people find lights or fellows, uh, kin, uh, like I, I hear from a lot of vets. I, I think of like, instead of a band bandied my, my unit, right? And there was a lot of things my people in my unit did that were not okay.

Sometimes I said something, sometimes I didn't. But by being true to myself, other people who I, who would confide in me, that they felt similarly. What could find me and give voice to that. I say that because I saw y'all perform twice Cornerstone and Papa Fest, and I've, I've told you this in some way, shape or form, like the, the, we're all just a bunch of animals going through rituals and music is so important and dancing is so important.

Um, I even think that's part of what Moses was demanding from Pharaoh. The word he uses chaga means to spin like a dance, like the whirling dervishes, let my people go to go worship, scare quotes. But really like it's a festival that let us go do our thing and we'll come back. I, I don't know if that was part of it, but like that's what Moses was asking for is to be free to do their thing.

Um, and I remember watching you perform it, it, I don't, I can't imagine myself. Performing on stage or off stage, like how I saw y'all play music. But seeing that helped me realize and helped me see, like literally realize to see something in real life that reflected what I felt inside. Um, and so IE and even as I say that, I'm like, I don't have any aspirations to be a musician.

Like I sing in the shower, I sing in the car, but like seeing how fully you committed to being the thing that was you while playing music allowed me to see that, allowed me to see it, to see that in real life and, and therefore kind of take ownership of that thing within me. Um, and I wonder if, if that kind of draws us back into our discussion of, of relics and texts and art, um.

And I, I'd really love to hear as a professor at the College of Idaho, it, I, I'm trying to remember the position was open, but you didn't have a PhD in anthropology, is that correct? Like it kind of just happened,

is that right? Right. Well, my PhD was in urban education with a focus in ethnographic research methods, so Okay.

There was the anthropology connection.

Gotcha. Yeah. Do you see some of that taking firmer shape now? Like do you feel anthropology is serendipitous in that, in that divine sense, like I was just, I was given biblical literature and so I started reading the Bible and really loving it. Do you feel similarly with anthropology?

Is that something that you really feel like you can invest yourself in and get excited about? Or is it still kind of, sort of a means to an end?

Oh, um. Great question. Um, no, I've certainly, you know, felt the serendipity of it and felt that in some ways this is what I've been doing all along. And in fact, I mean, just circle back to like having been in a band or having studied, you know, majoring in urban education but gravitating towards social science and philosophy, but the ethnographic research methods and sociology, there was this kind of interdisciplinary thing where, uh, and of course my interest in religion, um, all these aspects are like lenses through which we can look at humanity.

Mm-hmm. Um. One of the things I like most about anthropology is it's kind of flagrantly interdisciplinary quality. That subject matter is so broad. I mean it being interested in human beings, period. You know, I mean, past, present, future, everything human beings have ever done are doing or will ever do will be like under the, under the umbrella of anthropology.

And so I think, um, I'm fond of saying in my classes, you know, I think anybody can be an anthropologist or practices anthropology insofar as they ever ask anyone a question about their life. Yeah. If they're, you know, if you're different than I am and I express any curiosity in that difference and respect you enough to ask you about your experiences and trust that you have something to say that I can learn from.

Um. In my view, anyone who does that is already practicing anthropology. Um, and my favorite aspects of having been in a band, I mean, I did love the live performance and I, I do enjoy music to some extent, but I'm not, I don't identify myself as a musician or never was especially drawn to music. Um, but what I really loved about my role in the band is that I dealt with the, the lyrics, you know?

Mm-hmm. I didn't, I I, I wrote barely any of the chords or any of the music. I did very, very, very little next to nothing. I mean, but, but my focus was on the lyrics and the melodies to a lesser extent. But, um, it was really the words I was interested in, the meaning of the words, and then the ability to communicate verbally with other people and ask them in talking after the shows or even.

Someone broke a string and I would kind of interact with the people at the show while someone's changing their string. Those are actually my favorite parts of being in a band, was just engaging with other people and mm-hmm. Their ideas and getting to share my ideas and of course, being flattered by anyone else's interest in my ideas and the ego, you know, it pleasures of that, but I mean, beyond that kind of superficiality, like the real joy of being face to face with other human beings, sometimes for hours after our shows, just talking and listening and being together as human beings and learning from each other.

That to me, the way I see it, I was already practicing anthropology. Um, even while I was a, you know, being paid as a musician, I was kind of moonlighting as an anthropologist. So, you know, it just felt so, um, kind of natural to make that shift into being like formal. Title. Um, also I think it, it was something that I, I needed because of my own arrogance and kind of my, my self-righteousness that I was really sure that I had a lot of things figured out and I was sure that I was right about a lot of things and anyone disagrees with me is on the wrong side of this.

And anthropology pretty systematically as a discipline kind of undercuts are. You know, are, are self satisfied. Yeah. Um, you know, confidence in like the solitary rightness of our own perspective and like opens us up kind of relentlessly challenges us to open up to worldviews that, um, differ from our own, or even offend our sensibilities to try to see the logic in those worldviews or see the humanity in those humans, um, that, that, that do human life differently than I do human life.

And the presumption that that makes them wrong is suspect. You know? Yeah. It's become, it was just something I feel like I needed anthropology and in that way it kind of came along as a very health healthy corrective to my, um, disposition toward, toward, um, self-righteousness and my moral intensity. Which, which comes with it, the danger of.

Being judgemental and intolerant. Yeah. Um, and I wouldn't trade my moral intensity, but I'm trying to learn to maintain my moral intensity alongside humility. And I think part of that has to do with getting the ego outta the driver's seat and saying, well, there's nothing wrong with, with believing in the, the supremacy of love or the beauty of kindness or the rightness of justice.

Um, what, what goes wrong is if I start to get, let, put my ego in the driver's seat and presume that I am the harbinger or the, you know, a bearer of these things. Um, and then that they actually become quite the opposite. I think rather than unifying it become divisive. Mm-hmm. And harmful. Uh, and I just know this from my own experience.

I know that I've done that, and so I'm still in the process of trying to, um, learn those lessons. But my gosh, anthropology's been helpful to that, to that end

made me think that, um, I was listening to. Us without them, the podcast that they go through, your albums and the songs. I love it. I've been listening to it like a book, but it, I, I think that's where I heard that you didn't write a whole lot of the music.

It was just lyrics and, uh, when I was, when I got to see you guys at Cornerstone and Papa Fest, I was really interested in Ricky the drummer, and like watching how he was able to keep the beat. You know, drummers are like catchers on the baseball field. They do a little bit of everything and they're kind of, they're almost like the anchor.

They strike me as the anchor. I don't know. I don't, not in a band, but I think that kind of reinforces that, like that problem of like language and words, we've trained ourselves to just stuff them full of meaning. And so the lyricist and the singer gets that the, a disproportionate amount of the attention.

And it's not that you, you didn't ask for it, it's just like how we've. How we've unfolded culturally is expressed in these microcosms of a band. Um, or even like, you know, the military, the infantry being perceived as the highest of the high. Like, I'm sorry. If you take a step back, if you have a military that's all infantry, you're gonna lose every battle.

Like you have to have those other characters and or the, and the specialties and everything. Um, but when I heard that the music was less your purview, it allowed me and invited me to learn more about the band as a whole and how you had a part in that. But like, yeah, it felt like an invitation to like get into some of these other people who were responsible for this thing that you were a part of.

And even culturally, maybe we would describe a disproportionately high level of. Responsibility or agency to, but let's not lose sight of the forest, even though, you know, we may see the first couple of trees. Um, I have blasted through our halfway break, um, but we're coming up on, how are you doing on time?

'cause we're, you said you had to go at three 30, which I think is, is that now? Okay. I think we can, I think we could maybe conclude with what we have. Do you want to do one last, like five minute last words of wisdom or thoughts, parting thoughts?

Um, no. Uh, I, I don't have, um, I don't have any, uh. Words of wisdom, but, um, I'm enjoying talking with you and I can relate to you on so many levels.

And I feel like, uh, my guess is if I didn't have a time limit, we could just go on all day. Um, yeah. And it would be, uh, a delight. I guess we would like to just respond to the last thing you said about the intensity. Yeah. And like about our drummer. Like Ricky was such a powerhouse in that respect and like whatever I brought to, um, the band, you know, or whatever I was kind of doing when I was twirling around and screaming on stage, it was very much as part of that unit.

Yeah. And there was absolutely no way I was gonna get up there by myself on a stage and scream and flail around. You know, it was that kind of like mutual energy and us sharing that focus and, um, having that commitment to each other and working at it together and like feeding off of each other's intensity.

I also don't know if Ricky would've had that degree of intensity, you know, without Mike on guitar, if Mike would've had it without, you know, and on and on. So. I think, you know, it was very much a, a group effort. And, and, and that's another nice reminder for me to kind of keep my ego in check as far as like I was what the, the front man of a band or the lyricist.

I mean, really I wouldn't have been anything with that band without those other guys. And so, I mean, certainly not any of the intensity or the, the depth to which I was able to, you know, explore those ideas and then express them with such abandon. Um, it was really facilitated through. Through our community, through our relationships with each other.